Follows from: Evolution is Sampling Error

It seems a lot of people either missed my footnotes in the last post about effective population size, or noticed them, read them and were confused1. I think the second response is reasonable; for non-experts, the concept of effective population size is legitimately fairly confusing. So I thought I’d follow up with a quick addendum about what effective population size is and why we use it. Since I’m not a population geneticist by training this should also be a useful reminder for me.

The field of biology that deals with the evolutionary dynamics of populations — how mutations arise and spread, how allele frequencies shift over time through drift and selection, how alleles flow between partially-isolated populations — is population genetics. “PopGen” differs from most of biology in that its foundations are primarily hypothetico-deductive rather than empirical: one begins by proposing some simple model of how evolution works in a population, then derives the mathematical consequences of those initial assumptions. A very large and often very beautiful edifice of theory has been constructed from these initial axioms, often yielding surprising and interesting results.

Population geneticists can therefore say a great deal about the evolution of a population, provided it meets some simplifying assumptions. Unfortunately, real populations often violate these assumptions, often dramatically so. When this happens, the population becomes dramatically harder to model productively, and the maths becomes dramatically more complicated and messy. It would therefore be very useful if we could find a way to usefully model more complex real populations using the models developed for the simple cases.

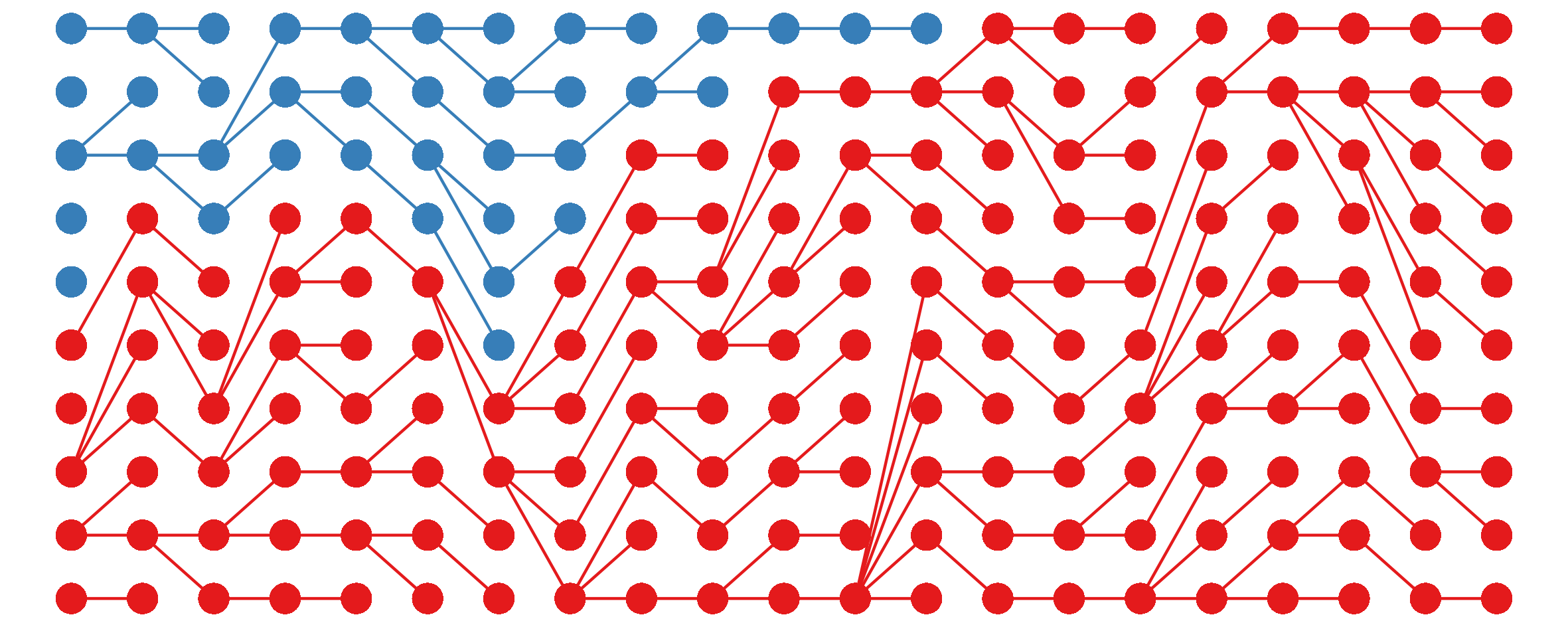

Fortunately, just such a hack exists. Many important ways in which real populations deviate from ideal assumptions cause the population to behave roughly like an idealised population of a different (typically smaller) size. This being the case, we can try to estimate the size of the idealised population that would best approximate the behaviour of the real population, then model the behaviour of that (smaller, idealised) population instead. The size of the idealised population that causes it to best approximate the behaviour of the real population is that real population’s “effective” size.

There are various ways in which deviations from the ideal assumptions of population genetics can cause a population to act as though it were smaller – i.e. to have an effective size (often denoted \(N_e\)) that is smaller than its actual census size – but two of the most important are non-constant population size and, for sexual species, nonrandom mating. According to Gillespie (1998), who I’m using as my introductory source here, fluctuations in population size are often by far the most important factor.

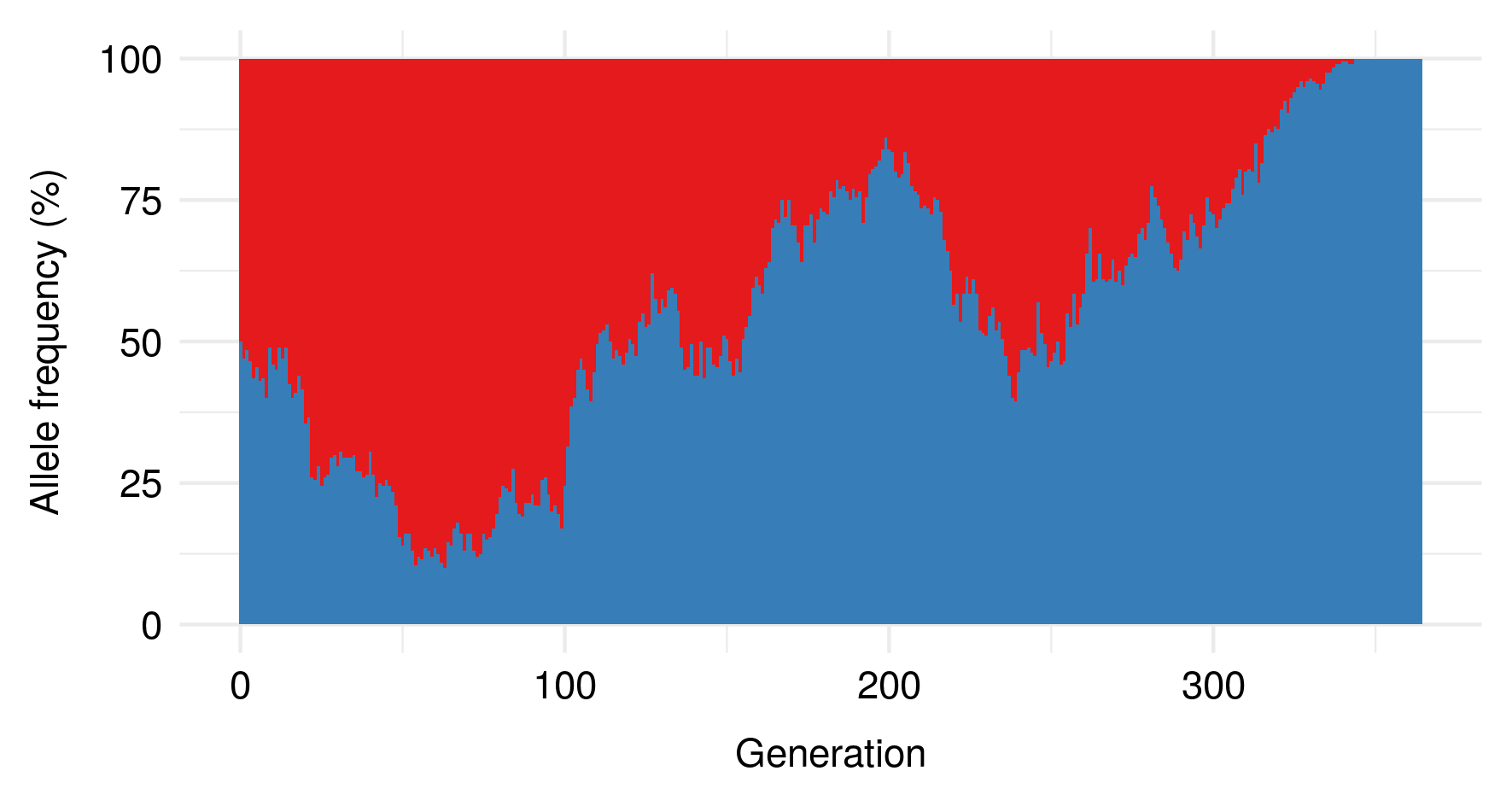

In terms of some of the key equations of population genetics, a population whose size fluctuates between generations will behave like a population whose constant size is the harmonic mean of the fluctuating sizes. Since the harmonic mean is much more sensitive to small values than the arithmetic mean, this means a population that starts large, shrinks to a small size and then grows again will have a much smaller effective size than one that remains large2. Transient population bottlenecks can therefore have dramatic effects on the evolutionary behaviour of a population.

Many natural populations fluctuate wildly in size over time, both cyclically and as a result of one-off events, leading to effective population sizes much smaller than would be expected if population size were reasonably constant. In particular, the human population as a whole has been through multiple bottlenecks in its history, as well as many more local bottlenecks and founder effects occurring in particular human populations, and has recently undergone an extremely rapid surge in population size. It should therefore not be too surprising that the human \(N_e\) is dramatically smaller than the census size; estimates vary pretty widely, but as I said in the footnotes to the last post, tend to be roughly on the order of \(10^4\).

In sexual populations, skewed sex ratios and other forms of nonrandom mating will also tend to reduce the effective size of a population, though less dramatically3; I don’t want to go into too much detail here since I haven’t talked so much about sexual populations yet.

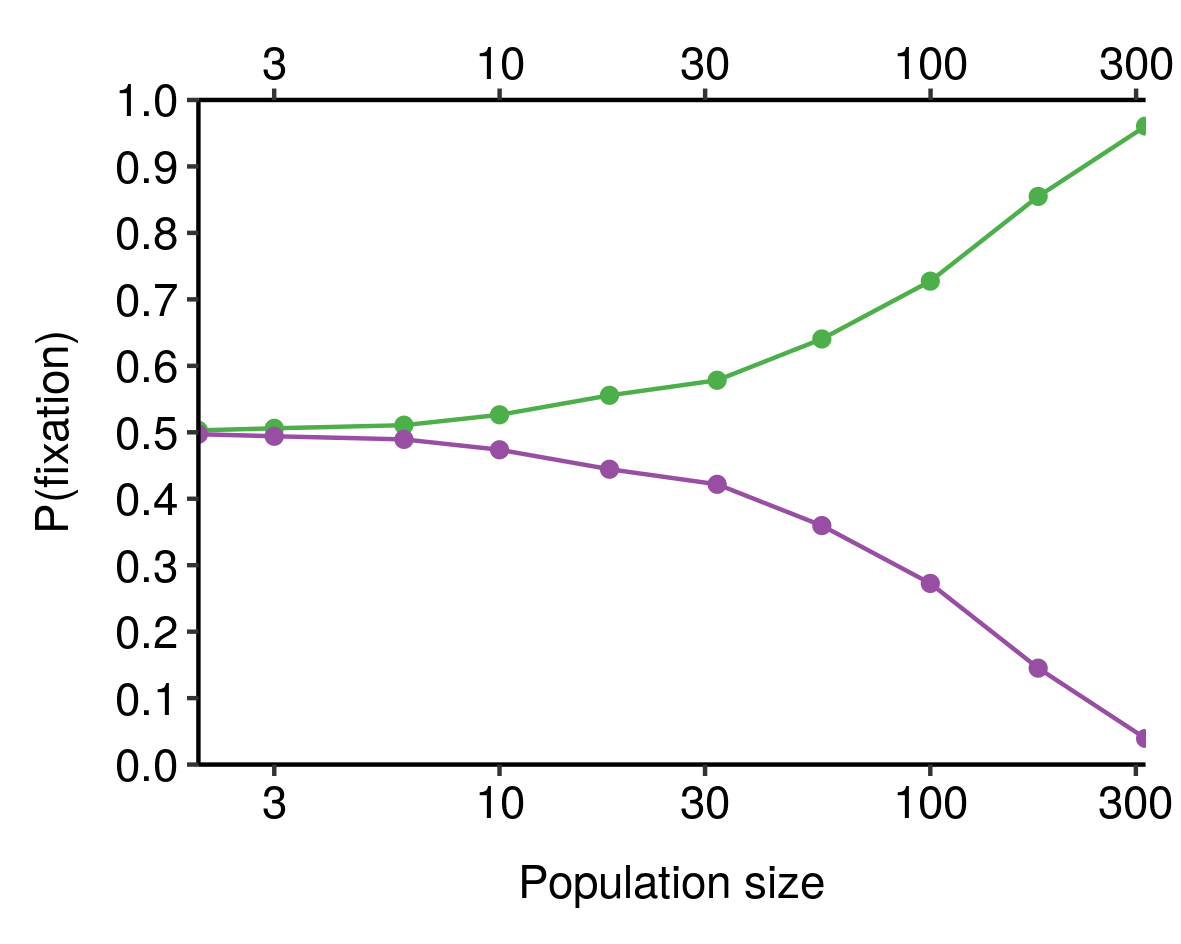

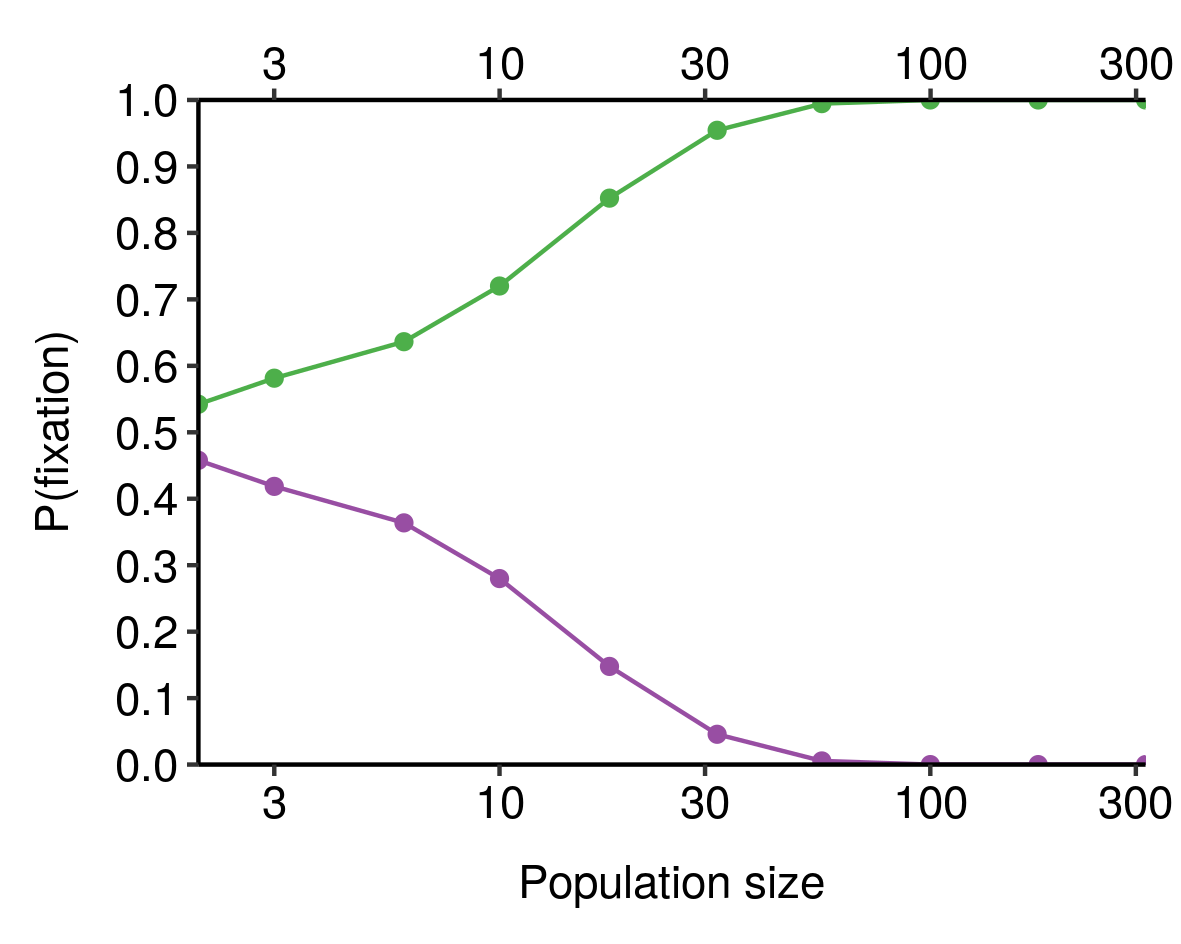

As a result of these and other factors, then, the effective sizes of natural populations is often much smaller than their actual census sizes. Since genetic drift is stronger in populations with smaller effective sizes, that means we should expect populations to be much more “drifty” than you would expect if you just looked at their census sizes. As a result, evolution is typically more dominated by drift, and less by selection, than would be the case for an idealised population of equivalent (census) size.

-

Lesson 1: Always read the footnotes. Lesson 2: Never assume people will read the footnotes. ↩

-

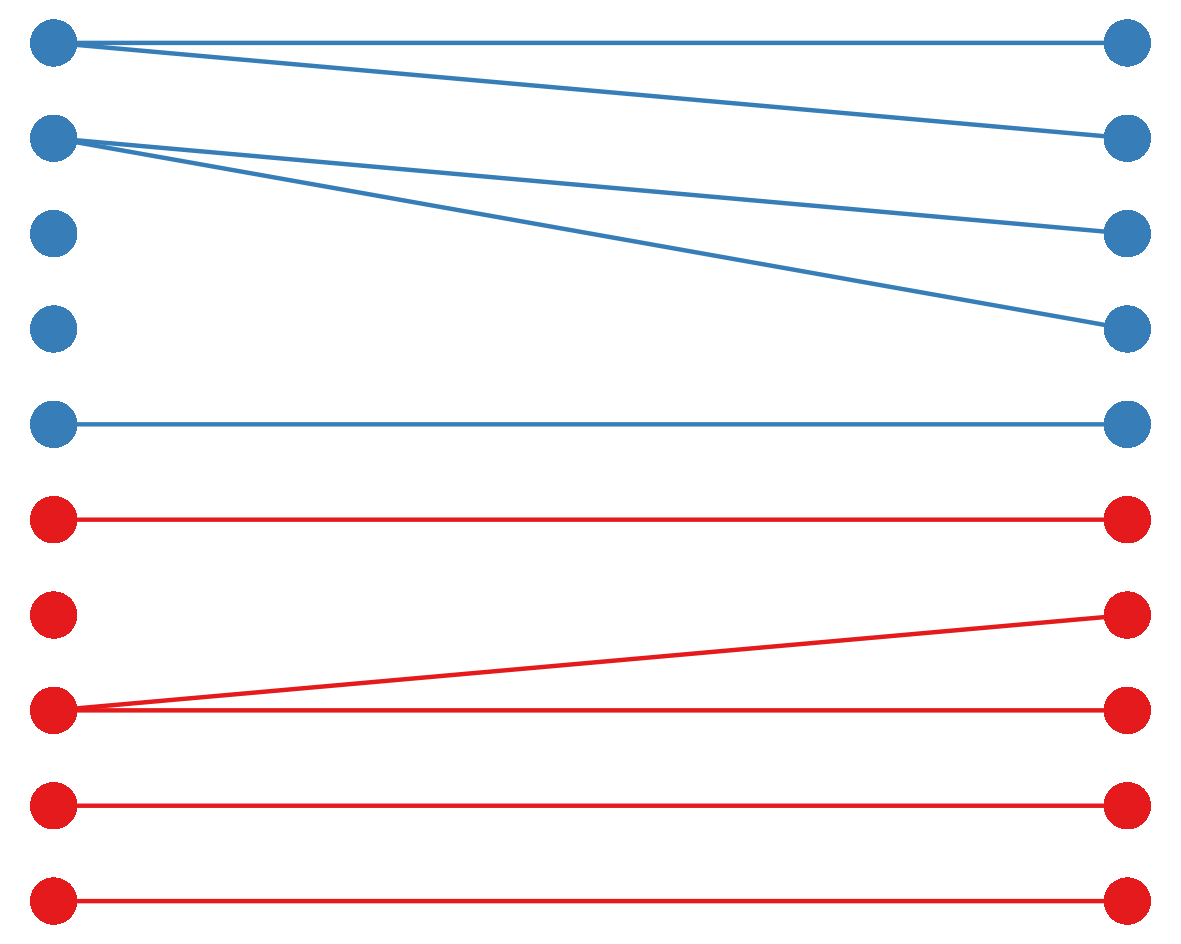

As a simple example, imagine a population that begins at size 1000 for 4 generations, then is culled to size 10 for 1 generation, then returns to size 1000 for another 5 generations. The resulting effective population size will be:

\(N_e = \frac{10}{\frac{9}{1000} + \frac{1}{10}} \approx 91.4\)

A one-generation bottleneck therefore cuts the effective size of the population by an order of magnitude. ↩ -

According to Gillespie again, In the most basic case of a population with two sexes, the effective population size is given by \(N_e = \left(\frac{4\alpha}{(1+\alpha)^2}\right)\times N\), where alpha is the ratio of females to males in the population. A population with twice as many males as females (or vice-versa) will have an \(N_e\) about 90% the size of its census population size; a tenfold difference between the sexes will result in an \(N_e\) about a third the size of the census size. Humans have a fairly even sex ratio so this particular effect won’t be very important in our case, though other kinds of nonrandom mating might well be. ↩

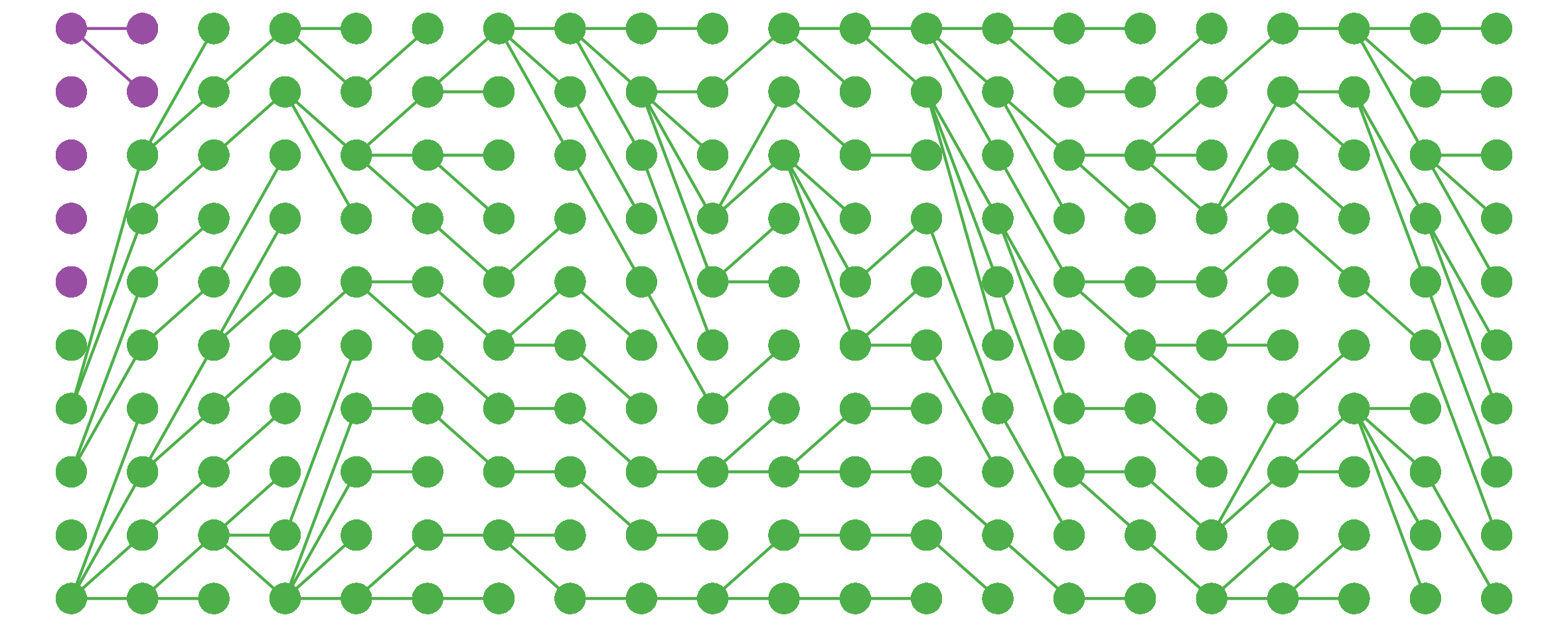

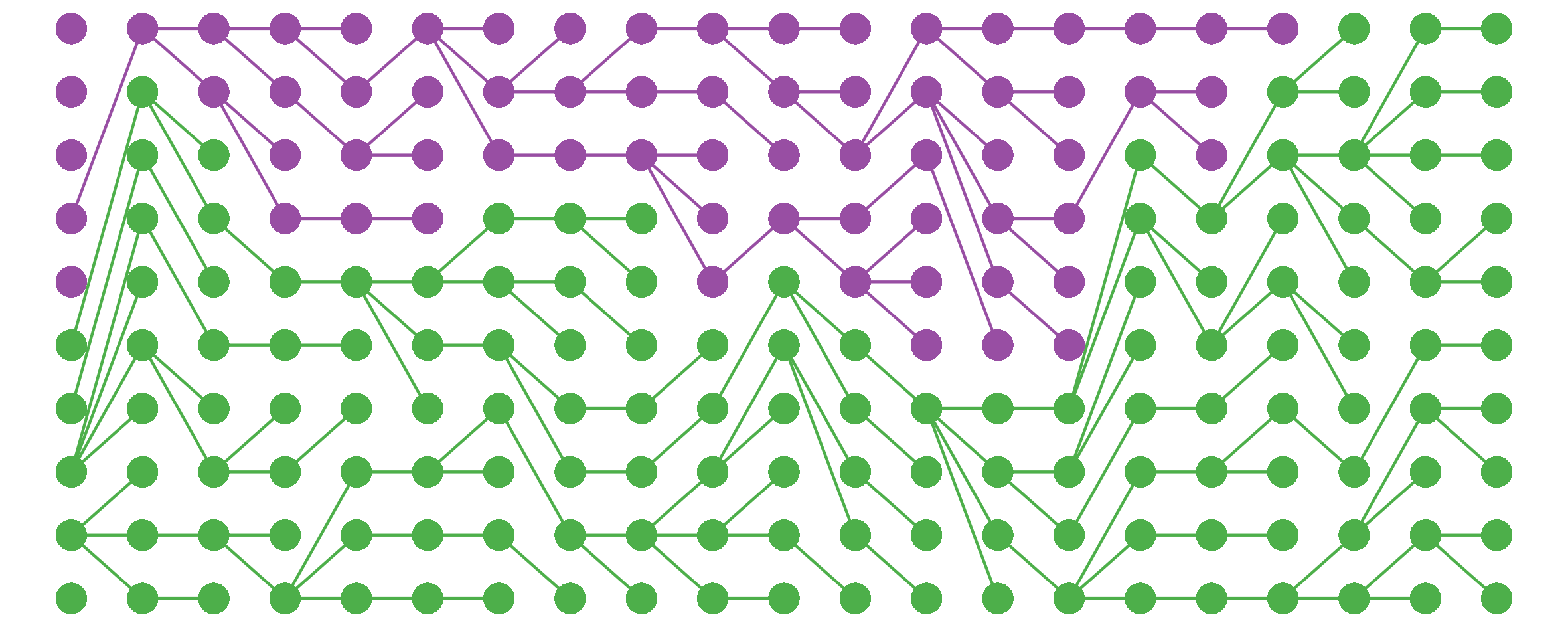

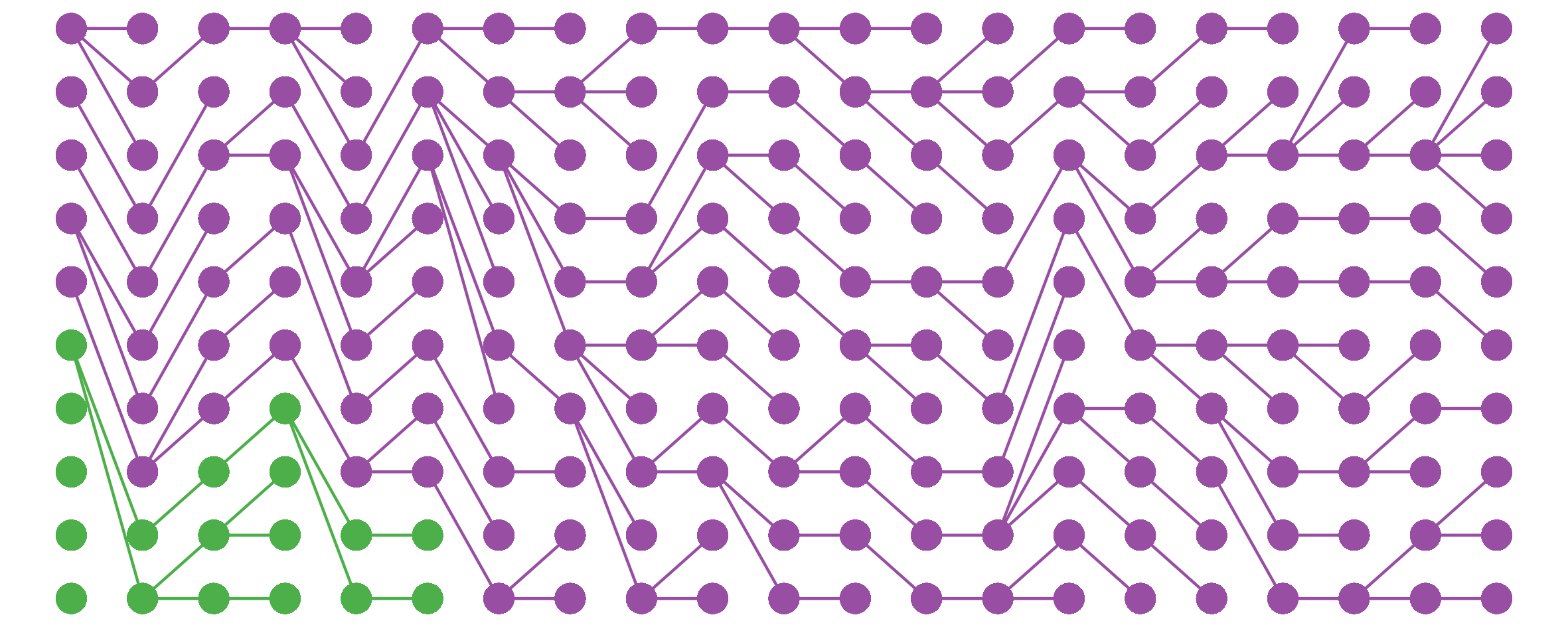

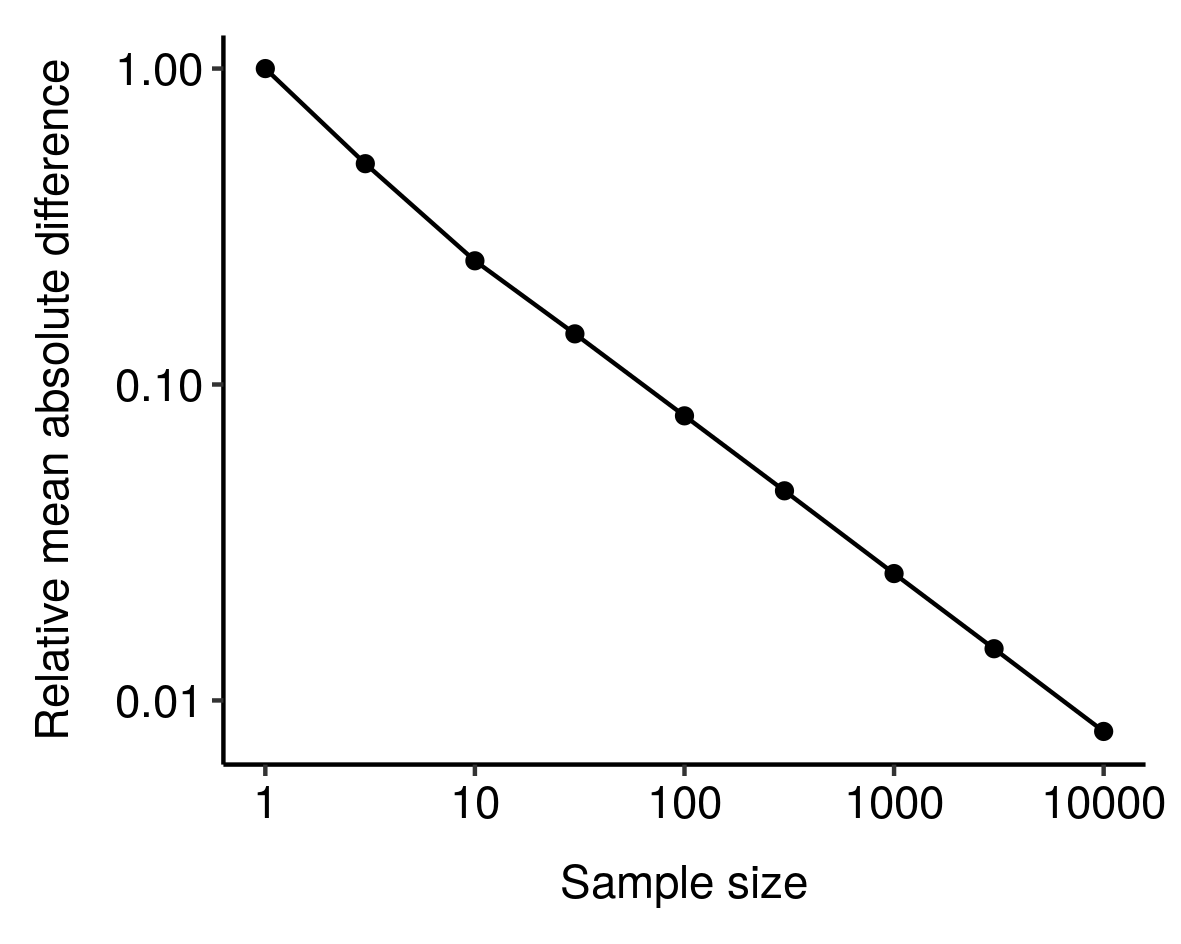

I noticed this from simulations and haven’t bothered to tease out the underlying mathematics here, but still, kinda cool.

I noticed this from simulations and haven’t bothered to tease out the underlying mathematics here, but still, kinda cool.