Over the course of this all-too-solitary year, a few different people have asked me for video game recommendations. I generally responded with overwhelmingly long lists that probably did more to scare them away than anything else. But with a long, dark winter approaching and the pandemic still keeping most of us at home, it seems like a better time than ever to explore a few new corners of the digital world. So, here’s a shorter list, in no particular order, of ten not-too-long, more-than-minimally-obscure games I really, really think you should play.

Return of the Obra Dinn

Once upon a time, Lucas Pope made Papers Please, a very stressful game about guarding the border of a totalitarian state. Then he disappeared for five years. In 2018, he resurfaced with one of the best games I have ever played.

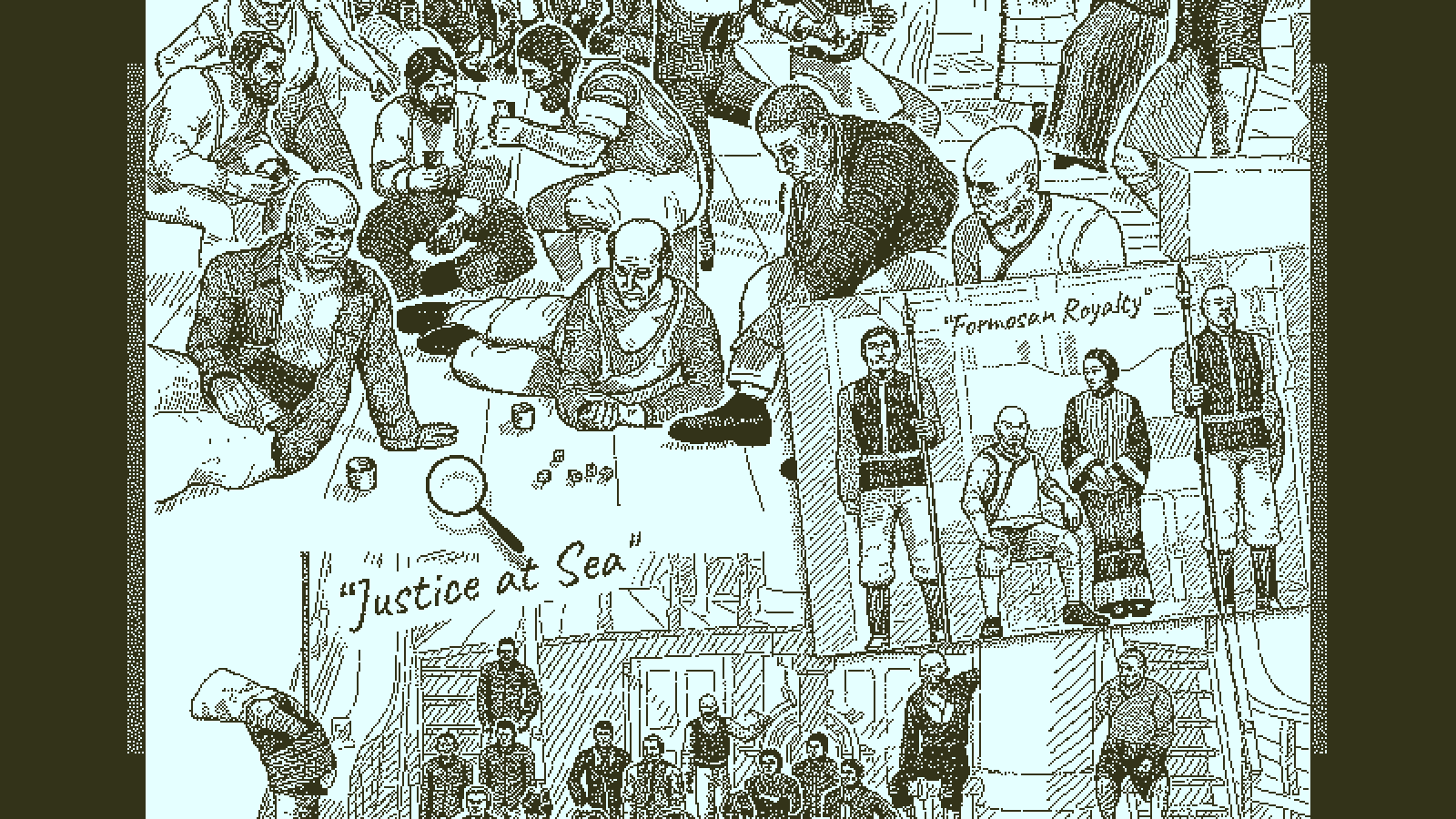

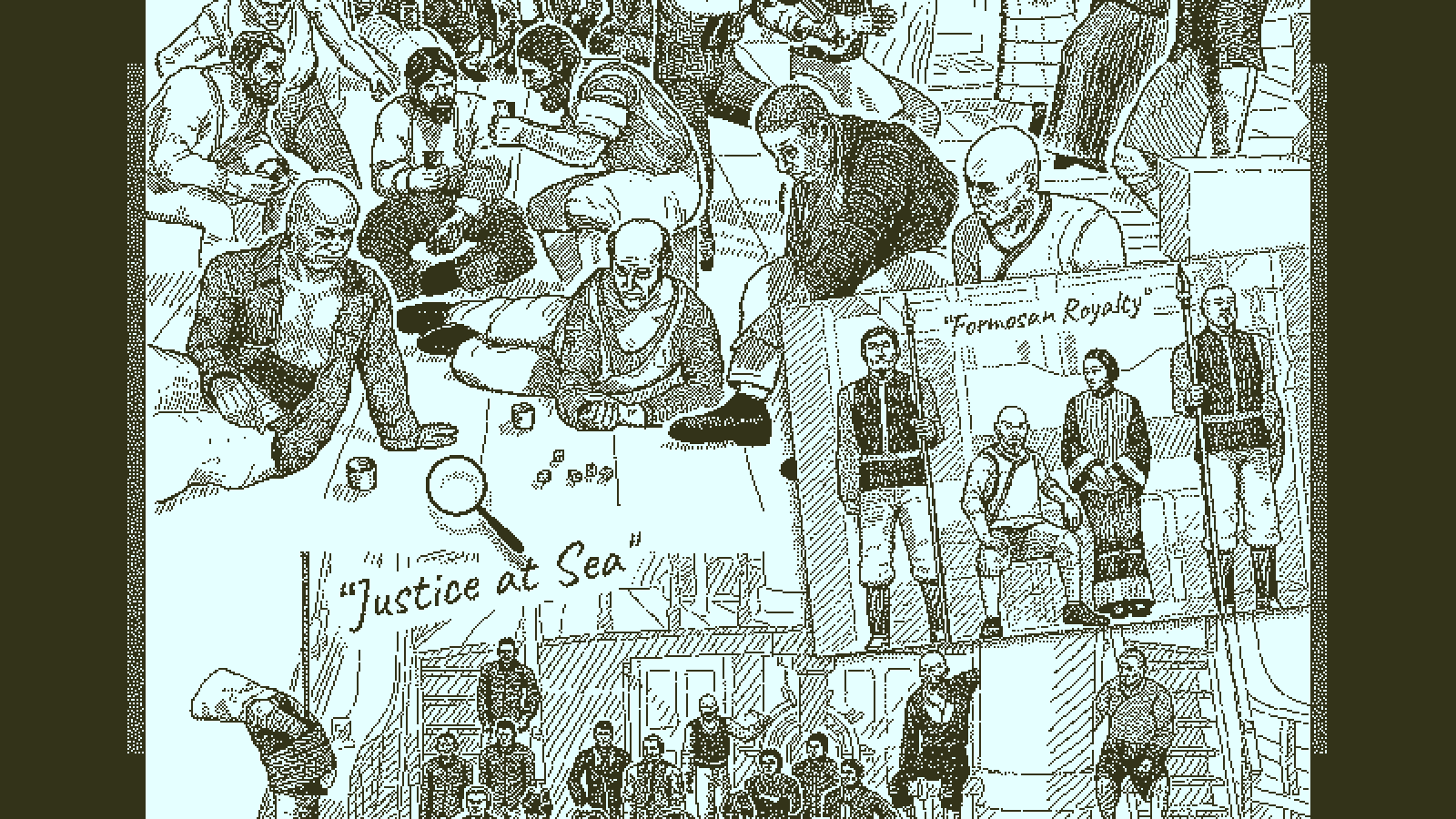

Once upon a time, the Obra Dinn set sail from England, bound for Formosa. Then it disappeared for five years. Now it has reappeared off the English coast, derelict, and the East India Company has sent you to find out what the funk happened.

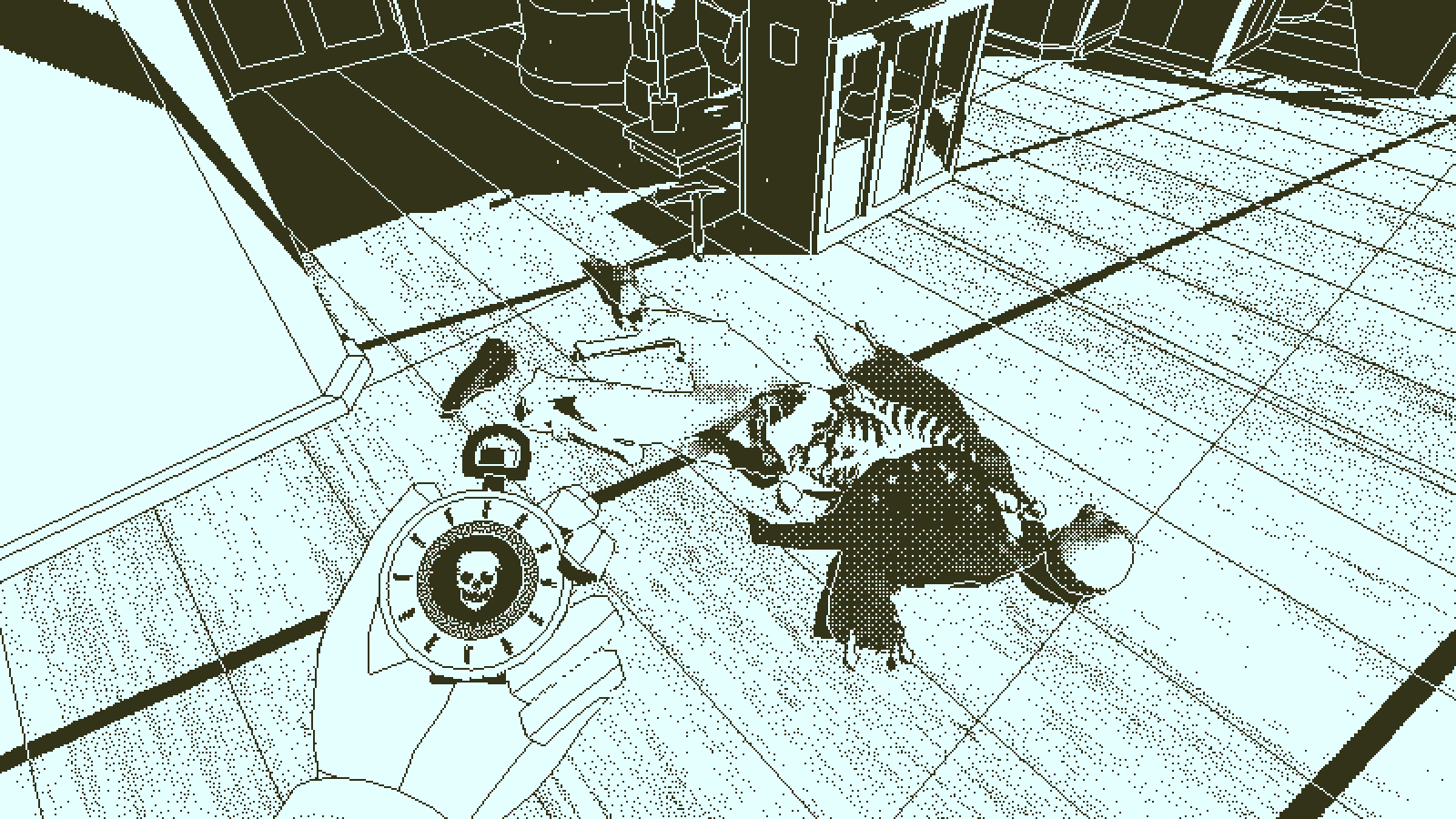

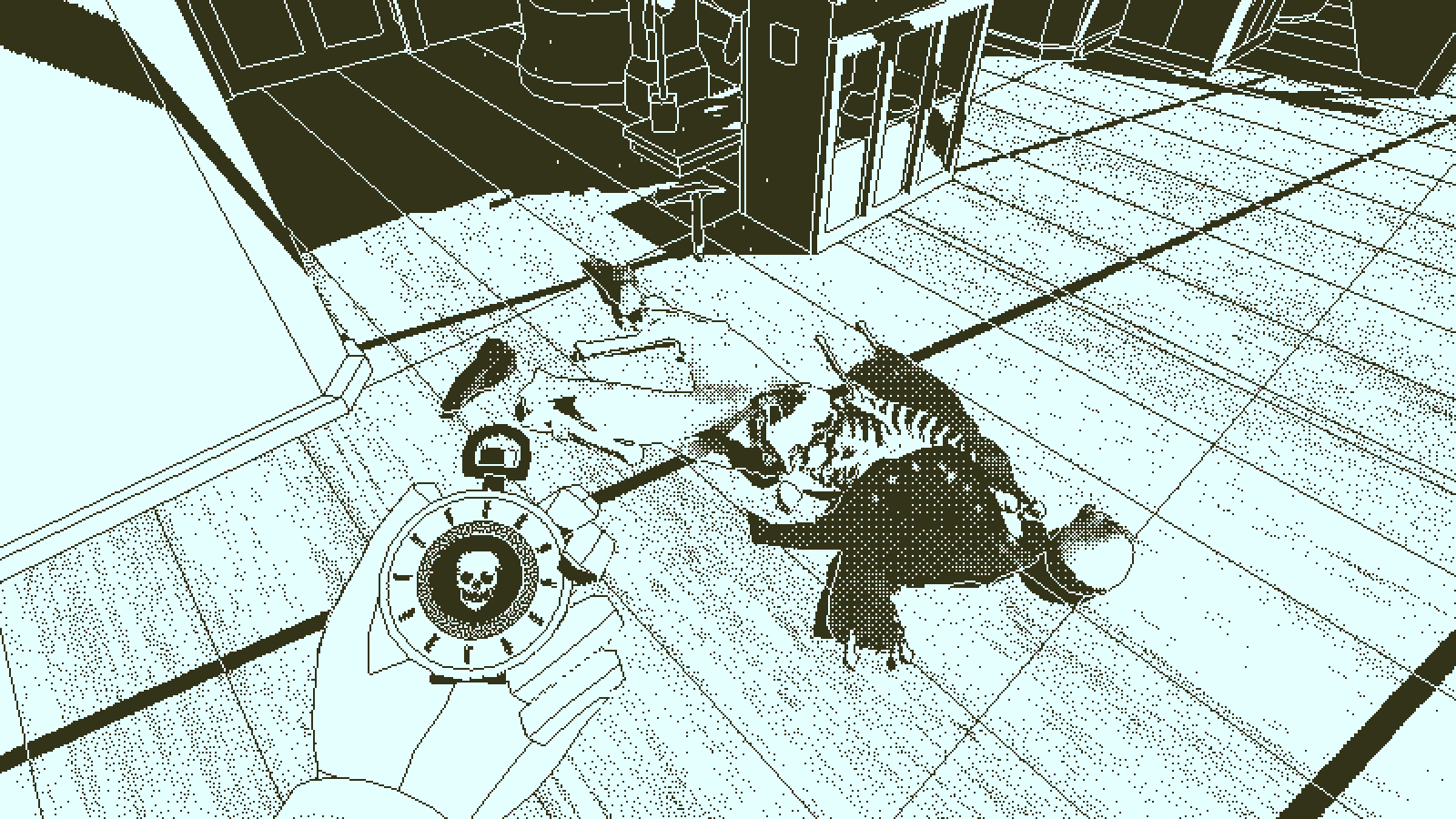

Armed with a ship’s manifest, a map of the ship, pictures of the crew, and a magic watch that lets you relive the last few seconds of a corpse’s life (standard issue for insurance agents in the 19th century), you must identify the fate of each of the 60 crewmembers. Oh, and the whole thing is meticulously rendered in 1-bit graphics.

In essence, Return of the Obra Dinn is one huge puzzle – perhaps my favourite puzzle in any video game I’ve played. By paying attention to everything that’s going on in every scene, you slowly piece together who is who, and what happened to them. You never need to guess: every identity and every fate, however obscure, is specified by some telling detail somewhere. It’s enthralling, especially once the story starts to get moving and you find out more and more about what happened to this misbegotten ship and her unfortunate crew. It’s hard to say more without spoilers; let’s just say that dithered explosions are surprisingly beautiful.

I played Obra Dinn straight through in about seven hours, while bedridden with a nasty cold. My incapacitated state made me take more leaps of guesswork than I might otherwise have done, which I will regret forever: the characters etch themselves into your brain so deeply that the game is basically un-replayable, so I’ll never get the chance to discover those answers the right way. If you take me up on this recommendation, learn from my example, and approach this game with the patience it deserves. It’ll probably still take you less than 10 hours (though no shame if it’s longer!), and It’s well worth the effort.

The Stanley Parable

“When Stanley came to a set of two open doors, he entered the door on his left.”

The Stanley Parable is a very, very hard game to review. Firstly, because it is so strange, so unlike anything except itself. Secondly, because it’s so difficult to write about any aspect of it without diminishing the experience of discovering it for yourself.

Which is not to say I don’t have thoughts about it! I wrote a whole thing here about all the different possible interpretations of The Stanley Parable and how they all, one by one, fall by the wayside, until all that is left is the thing itself, glorious and hilarious and free. But eventually I decided even that was too spoilery, and cut it in favour of this…thing.

Look, it’s really good, okay? It’s funny and smart and meta in all the best ways. It handles the question of choice in video games, which really is the only new thing videos bring to the table in terms of Art, with more wit and intelligence than any other game I’ve played. It’s not a long game, unless for some weird reason you end up playing it over and over and over and over and over again, but who would do something like that?

Luckily the free demo does a pretty good job of telling you whether or not you’ll enjoy the game, while…agh, just play the demo, it’s good – though not quite as good as the real thing.

There is, it is rumoured, an expanded version in the works, but since that version (a) is likely to be substantially different, and (b) has been delayed several times, you’re probably better off just taking the plunge now. If you’re anything like me, you’re unlikely to regret the opportunity to play it again in a year or two.

Shadowrun: Dragonfall and Shadowrun: Hong Kong

As a setting, Shadowrun confuses me. It really shouldn’t work. At first glance it’s the worst kind of incoherent coolism, the kind of setting whose operative principle is “Sure, why not?”. Want to play an elf that can do awesome magic and is also a wicked cool cyberpunk hacker? Want to control an army of mechanical drones, and an army of spooky elemental spirits? Sure, why not? Want to fight against a nefarious megacorporation who are also powering their evil machines with the souls of the dead? Sure, why not? Throw in the kitchen sink while you’re at it, might as well.

Yet, it works. In some ways it works much better than other fantasy settings, because it doesn’t assume that worlds different from ours must be technologically static. Magic re-emerged into the world, things changed and people died, and the world kept on going. Now it’s decades later, and the dragons have realised that you can get richer on the stock market than you can hoarding treasure, and the corporations have learned which problems are best solved with technology and which are best outsourced to the shamans.

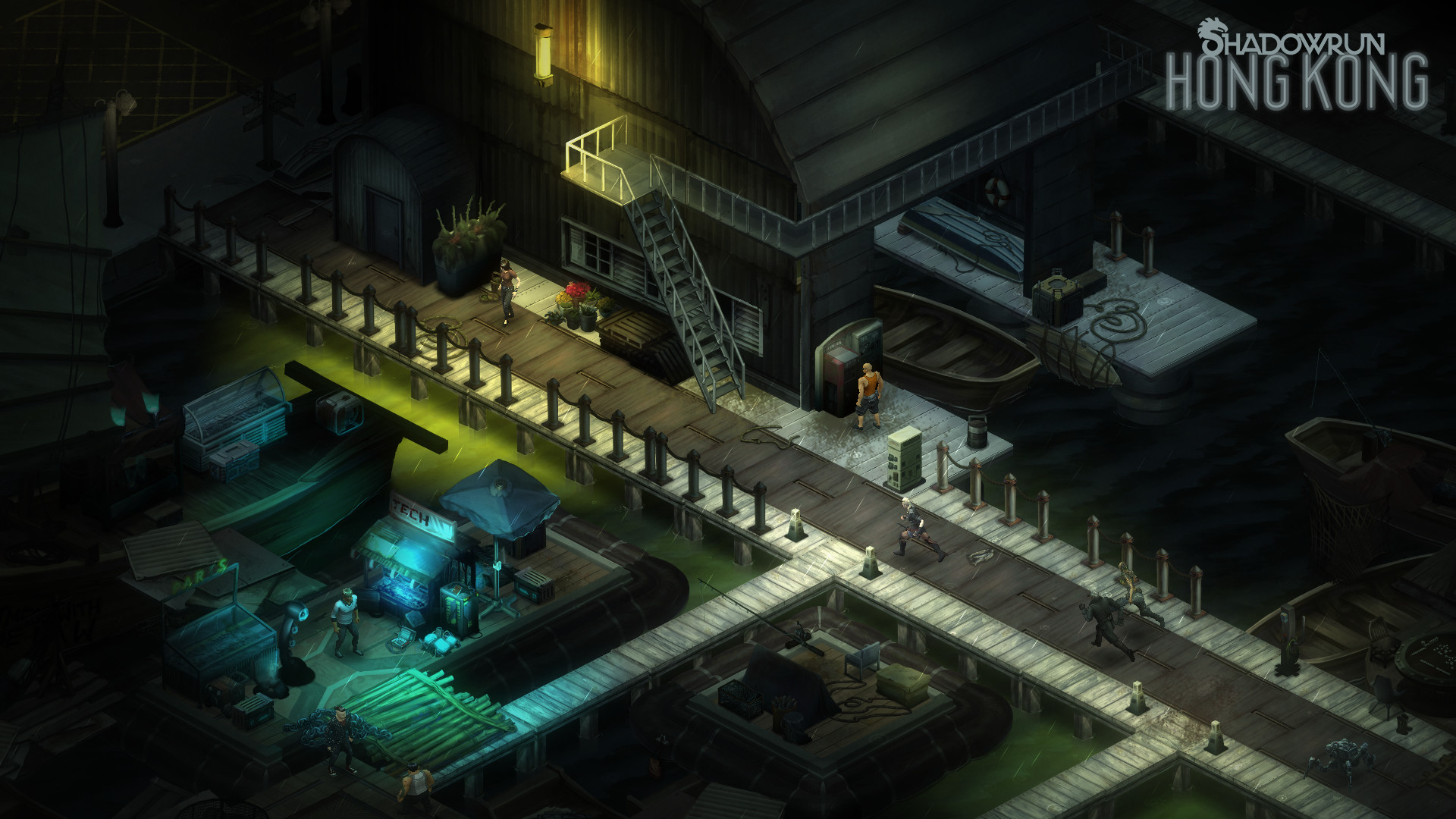

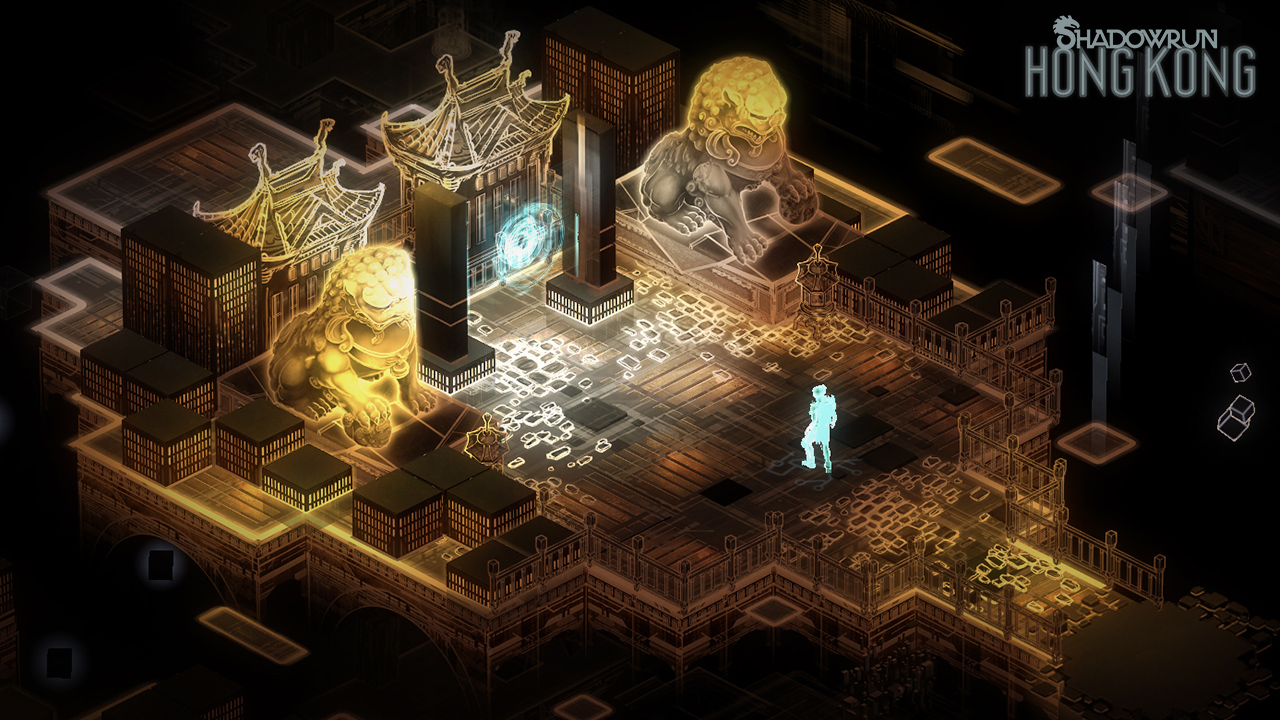

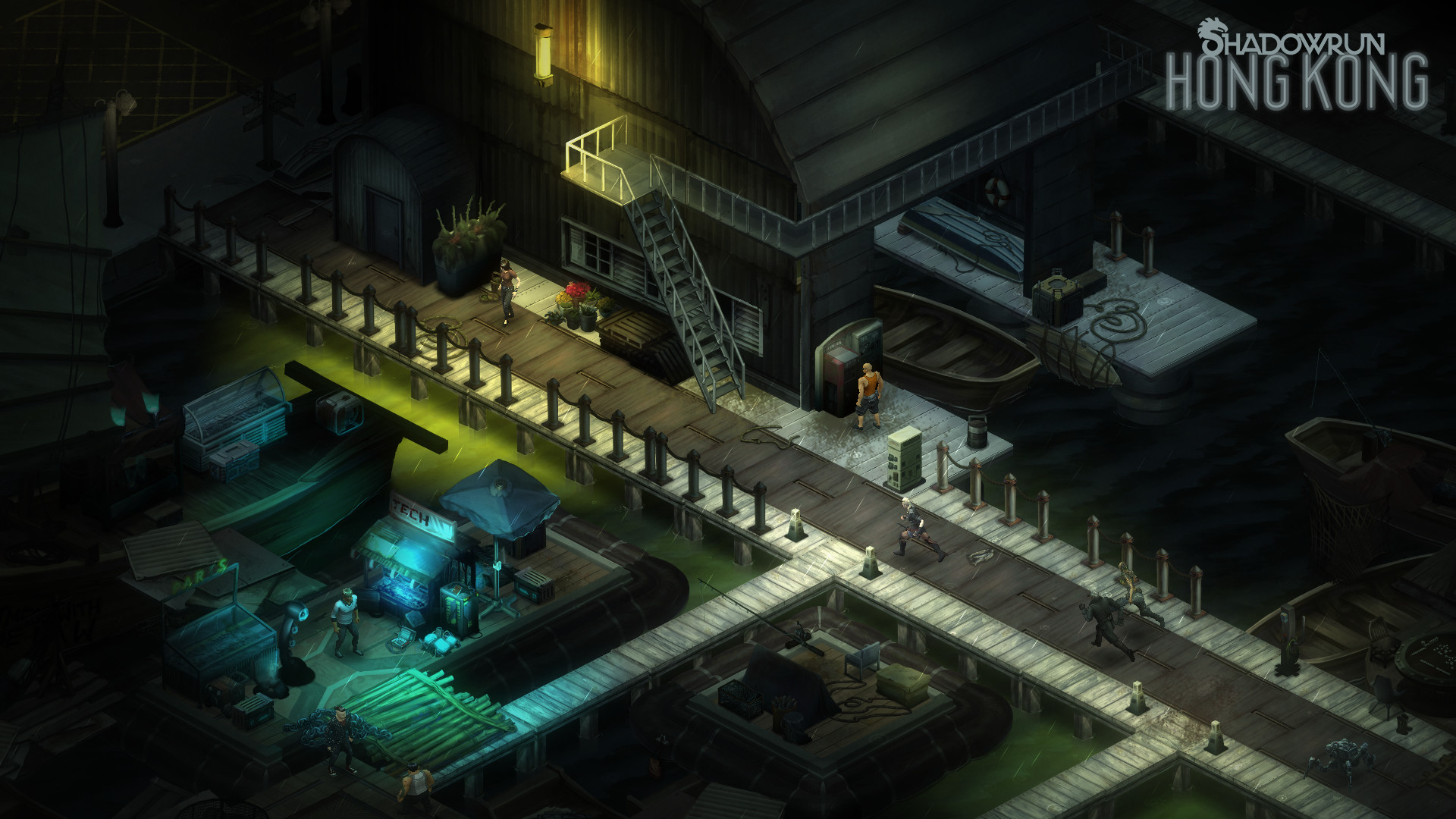

Harebrained Schemes’ first entry into the Shadowrun universe, Shadowrun Returns, was, in my opinion, not very good. But the two games it followed up with, Shadowrun: Dragonfall and Shadowrun: Hong Kong, are two of my favourite RPGs. Each is in a lovingly realised setting, with gorgeous backdrops, lots of interesting missions, and – especially in Hong Kong – characters I actually cared about. Crucially, neither outstays its welcome, with both being much shorter than your average (gargantuan) cRPG.

In gameplay and overall style, the two games are essentially the same, though Hong Kong is a little slicker. At the heart of both games is the classic Shadowrun concept: corporate espionage, exfiltration, the occasional assassination job if you have the stomach for it. It’s a nasty business, essentially organised crime, and most of the people who do it are nasty folks, but somehow the games always find a way for you to be a hero, if you want to be (in Dragonfall I was; in Hong Kong I wasn’t).

(It’s probably worth noting here that these are by far the most combat heavy of the games on this list (though not the most explicitly violent – that would be Obra Dinn), so if you’re not interest in having your cyberpunk worldbuilding interspersed with mowing down armies of mech-armoured, spellslinging goons then these probably aren’t the games for you.)

More important than the missions, though, is the world they inhabit, and it’s here that both games shine. Both achieve what many RPGs fail to, and make 2050s Berlin and Hong Kong (respectively) feel like living, breathing places – I can’t comment on the plausibility of the Hong Kong setting, but I found 2050s cyberpunk Berlin surprisingly believable, all things considered. Neither the cyberpunk nor the fantasy tropes are especially original by themselves, but in the interweaving of the two both games find that special something that makes the Shadowrun setting shine. Both also have surprisingly deep dialogue trees and character development for many minor NPCs; in Hong Kong in particular, I got quite invested in all the little lives going on around me in our little shanty-town home base.

In terms of setting and storyline, Hong Kong is probably the better game; in terms of combat I think Dragonfall offers a more interesting challenge, though that might just be because I built my character better in Hong Kong. Both are well worth your time and money.

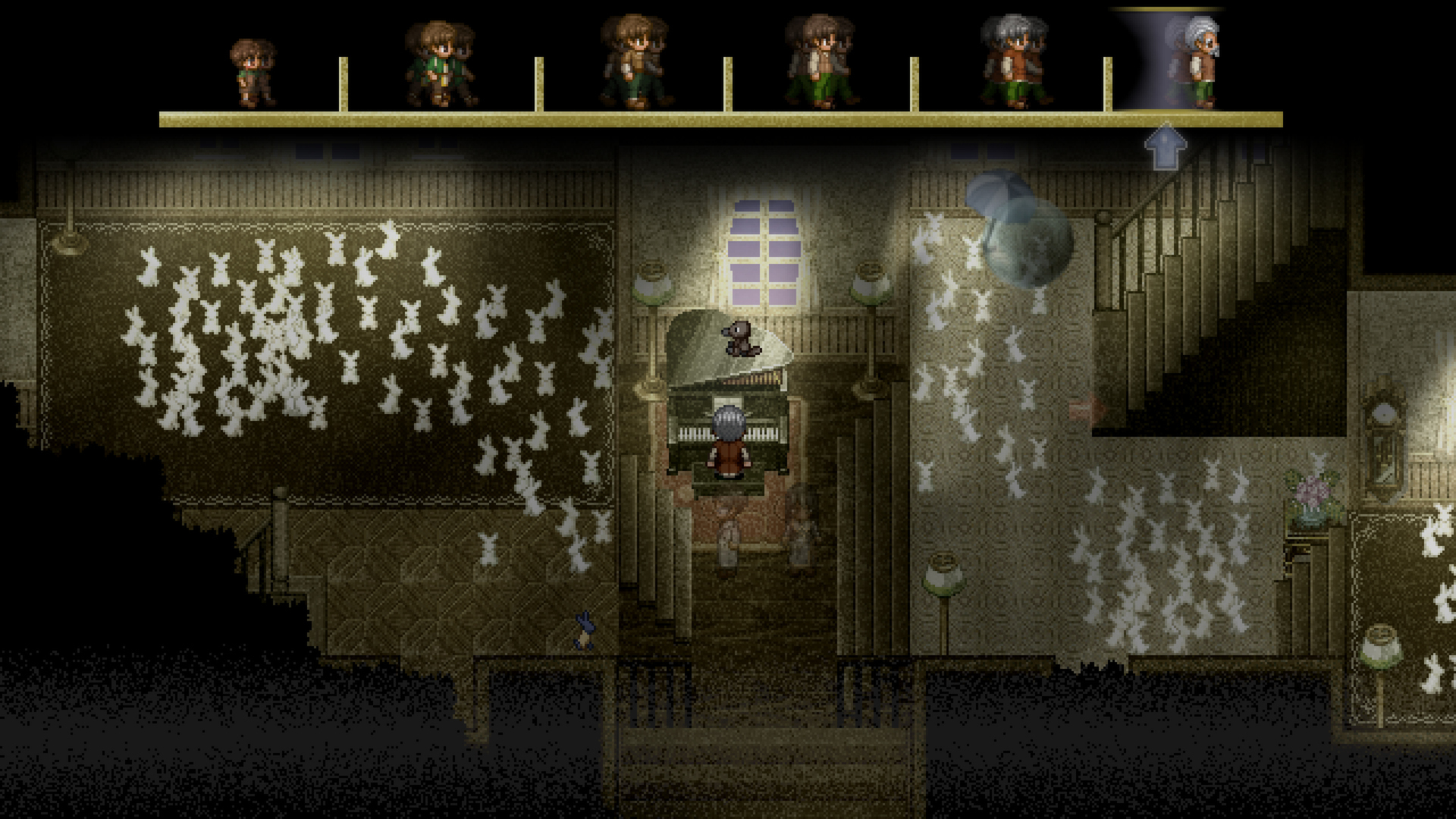

To The Moon

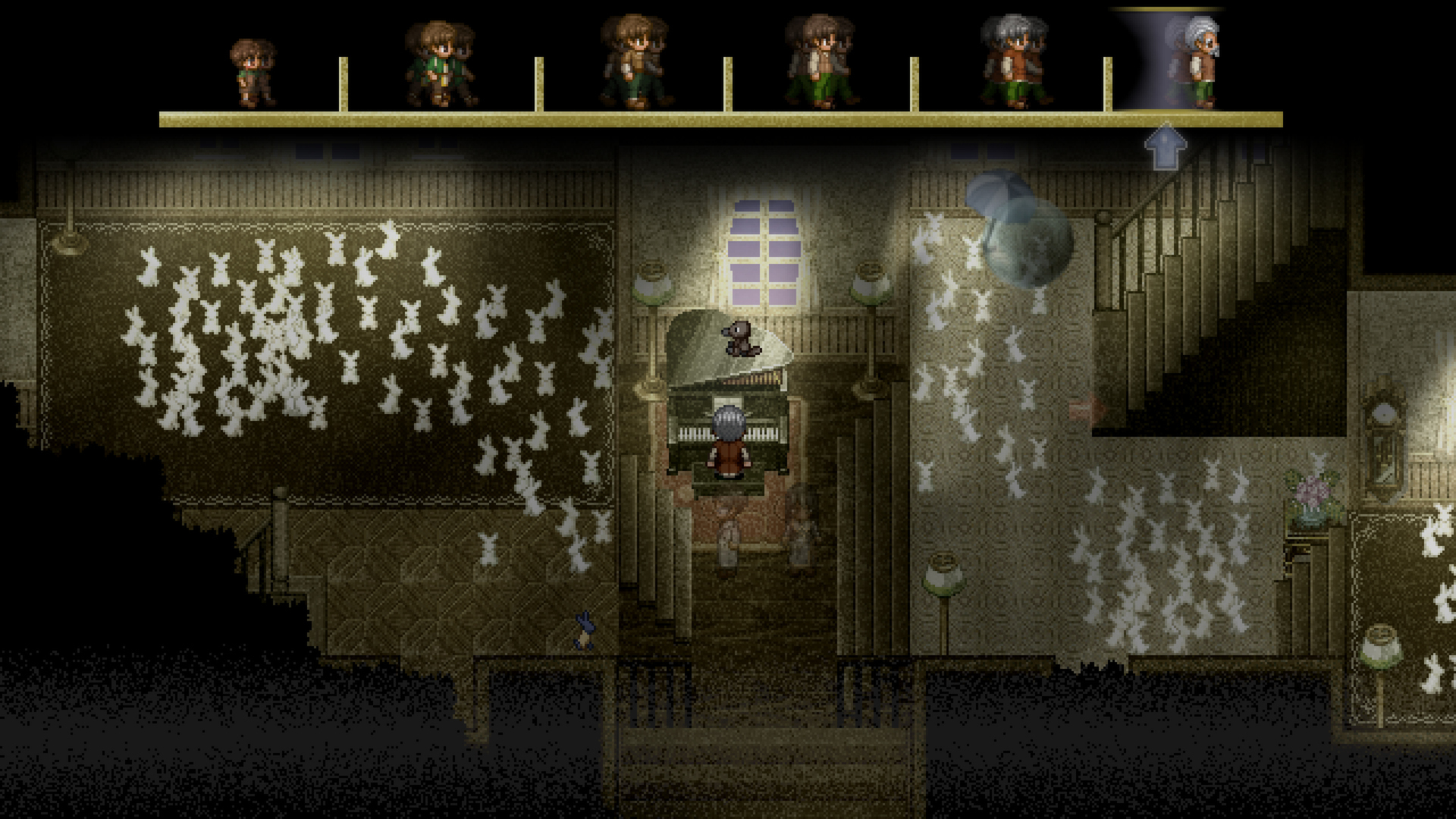

I don’t honestly remember whether or not I cried at the ending of To The Moon. I do remember feeling more emotionally conflicted about it than basically any other game I’ve played.

I got the game in some Humble Bundle years ago. Tried it, bounced off the graphics and the gameplay style, and forgot about it for years. At some point a friend mentioned that it was one of her favourite games, and I was interested enough to try it again. Turns out, abandoning it the first time was a huge mistake.

The setting: Sigmund Corp is a company that sells deathbed wishes. You want to be president, or marry the love or your life, or become a billionaire? Sigmund can give it to you. Just sign the contract, hand over the fee, and when you’re dying they’ll come and edit your memories, ensuring you die happy in the knowledge of a life well-lived.

Is that a…good thing to do? Hard to say. It’s a great thought experiment, though, and it’s excellently – and traumatically – handled here.

In To The Moon you play as a team of Sigmund scientists, dispatched to fulfill its contract with Johnny, an old man slowly dying in a big house. Johnny wants to go to the moon – simple enough, the kind of wish you handle all the time. The problem, as you quickly discover, is that he doesn’t remember why. So begins a traversal back though a lifetime of memories, trying to discover work out what to change to give Johnny whatever it is that he really wants.

Telling a story backwards is not a new trope, but it’s one that’s difficult to pull off well, and To The Moon does so with flying colours. It’s a story with no shortage of Themes, which it (mostly) handles with depth and grace, if not always with subtlety. The music is stunning, some of the best I’ve ever experienced anywhere, a fact made even more remarkable by the fact that it was all composed by the game’s lone developer.

There are wrinkles. I still don’t get on well with the graphics style, or the game engine. The humour is a mixed bag, sometimes charming and sometimes irritating. The game can’t quite bring itself to be a pure walking simulator, and insists on wedging in silly minigames that add nothing to the overall experience. But I’m willing to let all of these annoyances slide, because the thing in its entirety is so beautiful.

Dear Esther

Of all the games on this list, I expect Dear Esther to be the most YMMV. A game in which you slowly walk around a windswept island, with no run or jump buttons, no goal except to keep going, hear what the game wants you to here and see what it wants you to see…is not going to be for everyone. But at a pretty important time in my life, it was for me.

Of all the various emotions you might encounter over the course of a life, the one games are least well-equipped to reckon with is sadness. Excitement, joy, curiosity, wonder, fear, anger, disgust: all are well-represented in the gaming canon. But sadness, depression, grief are slow, heavy, aimless things, ill-suited to the high-intensity engagement of most popular games. Any game that would seriously reckon with these slow, tired, lonely feelings must itself feel slow and tired and lonely: hardly a recipe for a money-spinner.

Nevertheless there is a small but persistent line of games attempting to deal with these kinds of experiences. Of these, Dear Esther is the one that found me when I needed it.

You play as a man on a desolate island, alternately scenic and oppressive. You’re not initially sure why he’s here or what he’s talking about in his erudite-yet-roundabout narration, but it becomes clear he’s circling around some deep wound he doesn’t quite dare to touch. The music is beautiful, some of my favourite in gaming, expertly calibrated to the mood of the place. The first part of the game is admittedly a very slow start; but as you go on, and the narrator starts to lose his composure, and night begins to fall, the game becomes both more vivid and more intense. From about the halfway point on, I would call all of it – not just the audio – beautiful.

The game also rewards replaying: because it’s so short, because the narrator’s audio is somewhat randomised so you never hear exactly the same thing each time, and because the things you learn later cast substantial parts of the earlier game into a different light.

The rest is spoilers. Your mileage may vary. Perhaps it won’t speak to you. But it’s one of my favourite games, and it’s short enough and cheap enough that I think it’s worth trying.

Spider and Web

I couldn’t quite resist putting a text adventure on this list. There are actually quite a few text adventures I like a lot, but they are admittedly pretty niche, so I’m restricting myself to one full entry, and a few links. Andrew Plotkin’s Spider and Web made the cut because it tries to do something I’ve never quite seen in any other game, and does so well.

In general, we should expect text adventures to be at their best when they try to do things that are difficult to do effectively with graphics but can be done very effectively with words. Surreal humour is one example; creepy cosmic horror is another. Spider and Web is an example of a third thing: editing the narrative. Unreliable narrators are an underused trope in video games, one for which I’d generally expect text adventures to have a somewhat better time than graphical games. In Spider and Web, the unreliable narrator is you.

You begin in an unremarkable alleyway in an unspecified city, facing an unmarked door. Why are you here? You certainly don’t have anything suspicious in your pockets that could open such a door; in fact your inventory is empty. Oh, well. You turn and leave.

Bright lights. An interrogation room. Your interrogator is not impressed. Obviously you didn’t just turn and leave, because they found you behind the door. Try again.

On it goes. You get past the door. You infiltrate the facility. You turn left and burst into the laboratory complex! No, you would have been spotted immediately, and you weren’t caught until later. You must have gone a different way. Try again.

It’s a hard game, sometimes viciously so. You need to simultaneously solve the immediate puzzles of espionage, while also keeping an eye out for little ways to get the jump on your interrogators. Most of the time, they catch you at it; occasionally, they don’t. If you fail enough times the interrogator starts making little comments about how he’d expect a spy of your calibre to be a little smarter. The puzzle at the turning-point of the game is fiendishly hard – I’m pretty sure I used a walkthrough, or at least got some hints. But it’s also so clever I found it hard to fault it for being so difficult.

Like most text adventures, Spider and Web has the significant advantage of being free, at least if you discount the time required to get used to the basic conventions of the genre. You can run it on your command line if you’re feeling hacker-y, but dedicated software like Lectrote (by the same author as the game)can make the experience a little more friendly. If you like it, good news! There’s a whole little world of free interactive fiction waiting for you, much of it rather good.

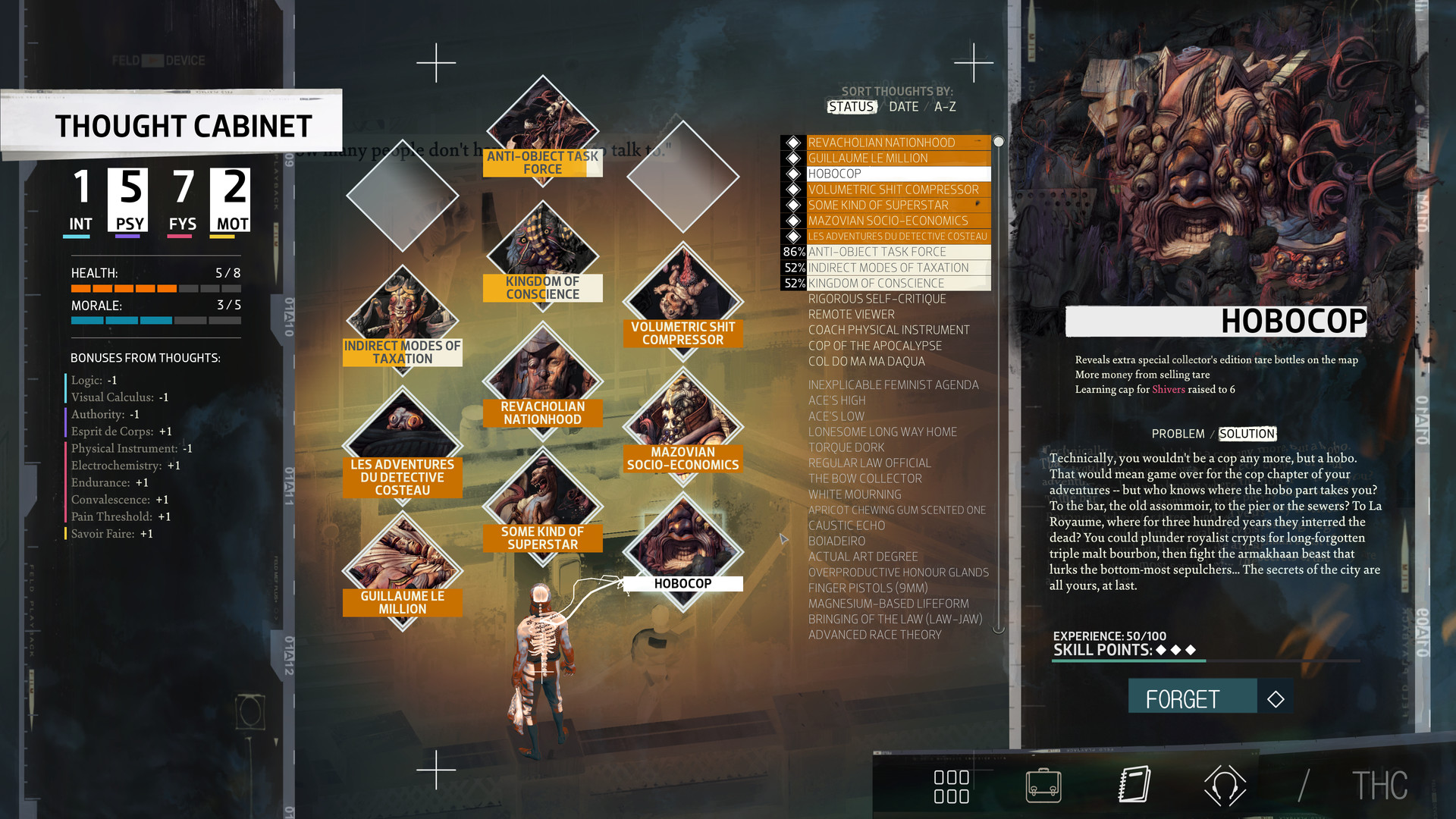

Disco Elysium

Okay, back to the world of pictures.

Of all the games on this list, Disco Elysium is the only one I discovered this year. I picked it up at the height of the first COVID wave, in the midst of my worst depression relapse for years, on the advice of a rather odd review in Rock Paper Shotgun. I needed to stop thinking for a couple of days and play something interesting. Usually when I decide to buy a new game it takes me several tries to find one that hooks me; this time, somehow, I got it in one.

It’s actually quite easy to describe Disco Elysium in a few words: it’s a dialogue-centric black-comedy not-quite-sci-fi police-procedural RPG.

Okay, that was quite a few words, especially if you don’t count the hyphens. The fact is, while many individual aspects of Disco Elysium can be seen as quite traditional, their combination is very original indeed.

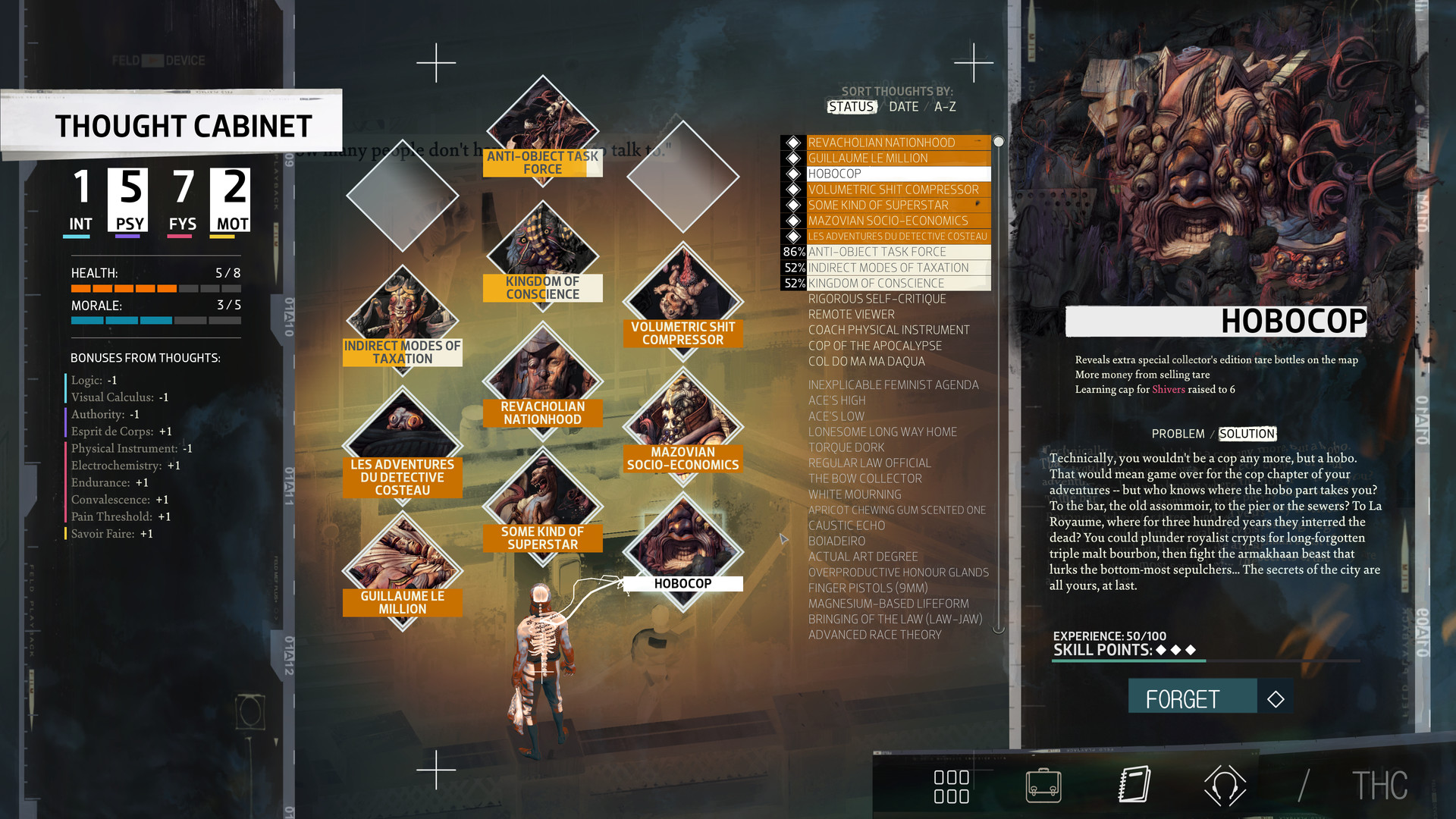

Firstly, it’s funny. Much funnier than any other RPG I’ve played. I laughed out loud quite a few times, and spent much of the rest of my playthrough smirking. Most of that humour comes from the shenanigans of your player character’s deeply messed up inner psyche: in Disco Elysium, your skill points represent both abilities and facets of yourself, and the more points you put in one facet, the more liable that facet is to butt in at inopportune moments.

Put points into Authority and you become more imposing, but also more boorishly status-obsessed. Put points into Inner Empire and you get more imaginative, but more prone to tear off on wild flights of fancy. The different aspects have their own voices, sometimes even their own voice actors, and their frequent internal disagreements are very entertaining.

The rest of the humour comes from the game’s huge cast of NPCs, many of whom are delightfully catty. Because that’s the second thing about Disco Elysium: it’s political. And not in the regular right-great-wrongs kind of game politics, but the grubby, down-to-earth, endlessly-argued-about, real-world kind of politics. You can even pick your own politics…to some degree. I went for a combination of moderate and libertarian, but rather than manifesting as a kind of moderate capitalist, my character lurched wildly between mealy-mouthed do-nothingism and unabashed greed-is-good Randianism, to the great confusion of my long-suffering sidekick.

I’m actually not sure where the game makers’ own political sympathies lie, which is its own kind of triumph: I think they’re probably self-aware leftists, but I wouldn’t bet much money on it. The leftist characters in the game certainly aren’t treated any more kindly than the rest; if anything, the reverse is true. The only group the game seems to have nothing but contempt for (other than the racists) are those who try to avoid politics altogether by agreeing that everyone makes some good points.

Anyway. The plot of Disco Elysium takes the form of a police procedural, investigating a politically charged murder in a gruesomely poor part of a rundown city. Oh, and to keep things interesting your main character has the kind of retrograde amnesia you only ever get in fiction, and needs to work out who the hell he is along with everything else. The setting of Disco Elysium is…odd. Unsettling. In many respects, it is a world far more like our own than the settings of most RPGs, while in other respects it is a very alien place. I don’t think I would like to live there, but I cared about the people who do.

The gameplay of Disco Elysium takes the form of an RPG of sorts, though one based entirely around dialogue and skill checks, with almost no combat in the traditional sense – no point where one set of rules gives way and another, more violent set of rules takes temporary hold of the world. Since the main turn-off of most RPGs for me is the way they scatter a perfectly good plot amidst dozens or hundreds of hours of goblin-slaying, this is fine by me.

All in all Disco Elysium is my favourite new game since…well, since Return of the Obra Dinn, to be honest, which is only about two years’ distance. But still, it’s a very good game and I strongly recommend it, especially to those of you who wouldn’t normally consider playing an RPG but are interested in trying something different. At the very least, it’s made ZA/UM one of the very short list of developers I’m actively keeping an eye on, waiting to see what they do next.

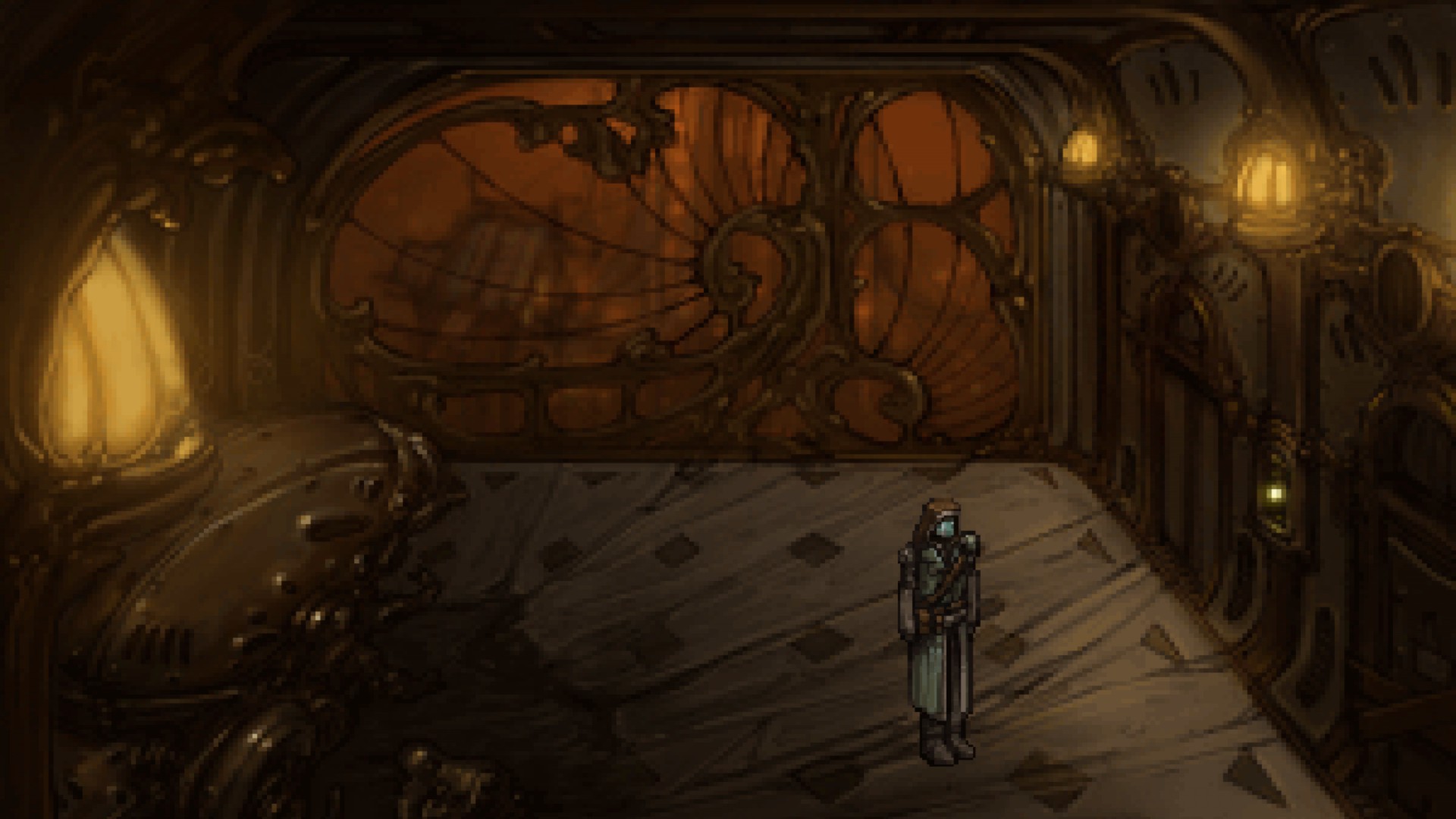

Primordia

In the world of modern-but-retro point-and-click adventure games – a world that’s been undergoing a modest revival over the past decade or so – Wadjet Eye Games is king. As a fan of such games I’ve played and liked most of their line-up, both as developer and as publisher, so picking a game to recommend here was a conundrum. Their best game is probably Technobabylon, a huge and sprawling cyberpunk mystery story with many characters and many – perhaps too many – creative mechanics. But Technobabylon isn’t my favourite Wadjet Eye game. That honour would have to go to Primordia.

I thought that was a controversial opinion. Back when I got Primordia (for cheap in a GOG sale, as I recall), it had received mostly lukewarm opinions from critics. Many said that the story didn’t hold together that well, or that the comedy sidekick was kind of annoying (both true). But I see now that it has 97% positive reviews on Steam, which is flabberghastingly high, so apparently it’s not as controversial an opinion as I thought.

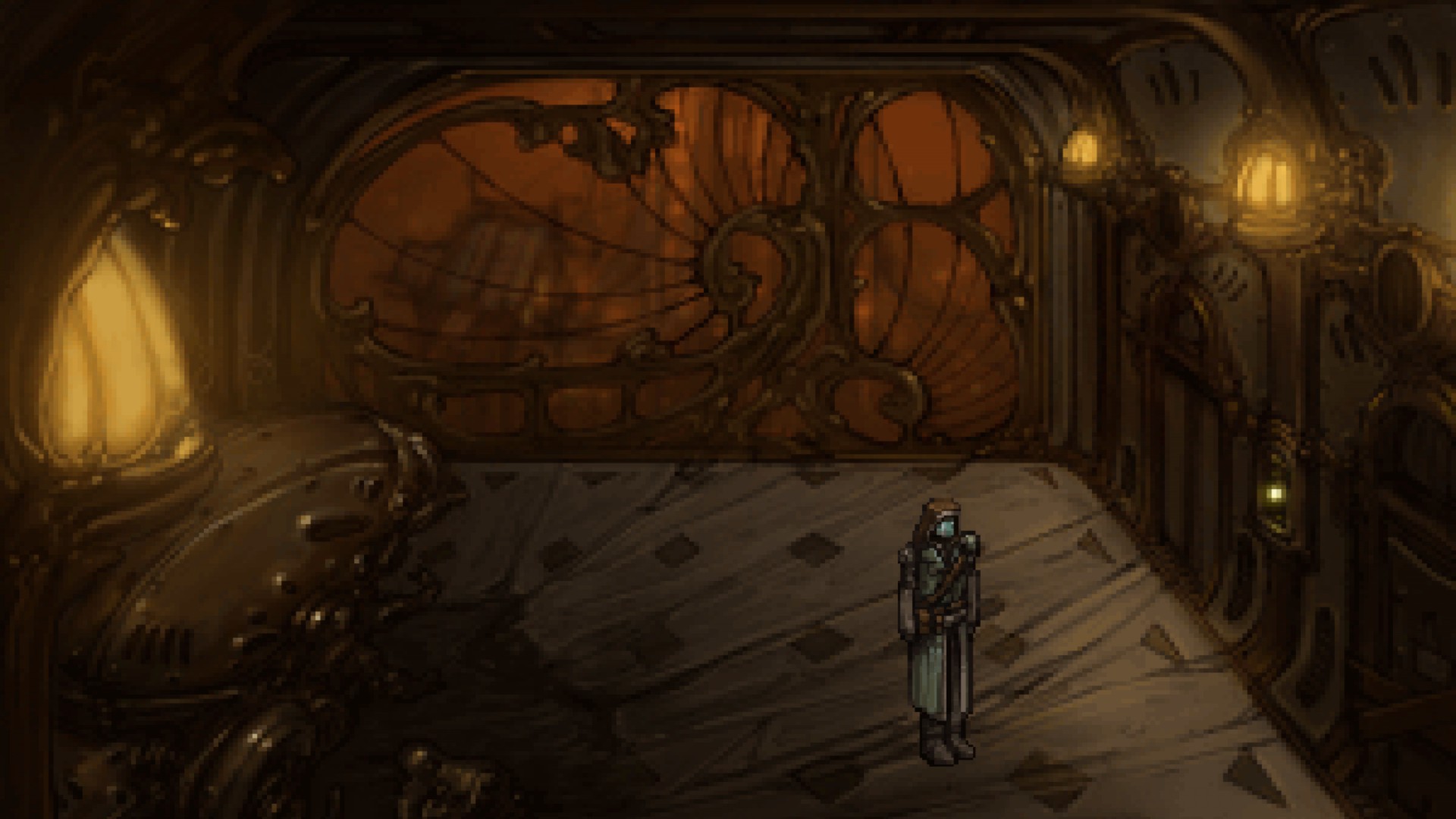

Agh, I’m watching the trailer on Steam now and it’s giving me chills. I love its aesthetic. That melancholic, rusty intricacy gets me every time. The humans have gone, and left behind only lost little robots and haunting music.

Perhaps I should step back.

In Primordia, you play as Horatio Nullbuilt, a lonely robot in a crashed airship in a desolate, war-scarred landscape. You spend your day scavenging parts, keeping yourself alive and trying not to think too hard about the big robot city nearby, a city that saturates the airwaves with its propaganda, a city you hate without knowing why. But one day, when a robot from the city cuts its way into the ship and steals your power core, you have to choose between joining the rest of the landscape in slow, fatal decay, or reckoning with your hatred, and your history.

That’s how I’d’ve put it, anyway. Maybe that’s why they don’t pay me to write blurbs for video games.

There is so much about Primordia that doesn’t make sense. Almost all the robots are obviously just metal humans, totally unbelievably like us in every respect. The history of Metropol barely holds together. Many key plot points hang on slender threads of suspended disbelief. But I don’t care because I love it all. I love the music. I love the mellifluous voice of the antagonist and the husky robotic tones of our hero (voiced by the narrator from Bastion!). I love the decaying, rust-ridden world. I love the totally implausible culture the robots have built for themselves since the humans went (especially the surnames, let me tell you about the surnames…except don’t, because spoilers). I love the great old robots of the city, vast and slow like ents of steel and silicon and rust, and the ruthless political games they play.

I’m baffled that a game this short could pack so much into itself that it keeps unspooling in my memory, all these years later. Somehow, so much more of it has lodged in my memory than usual that my mind, used to reconstructing big experiences from tiny slivers of memory, assumes there must really have been far more of it than there was. But that in itself tells you how memorable it was, how well it is the thing that it is.

I hear the developers have a new game out soon, also published by Wadjet Eye. I’ll definitely be keeping an eye on that. In the meantime Primordia is so old and cheap now that, really, what excuse do you have not to play it?

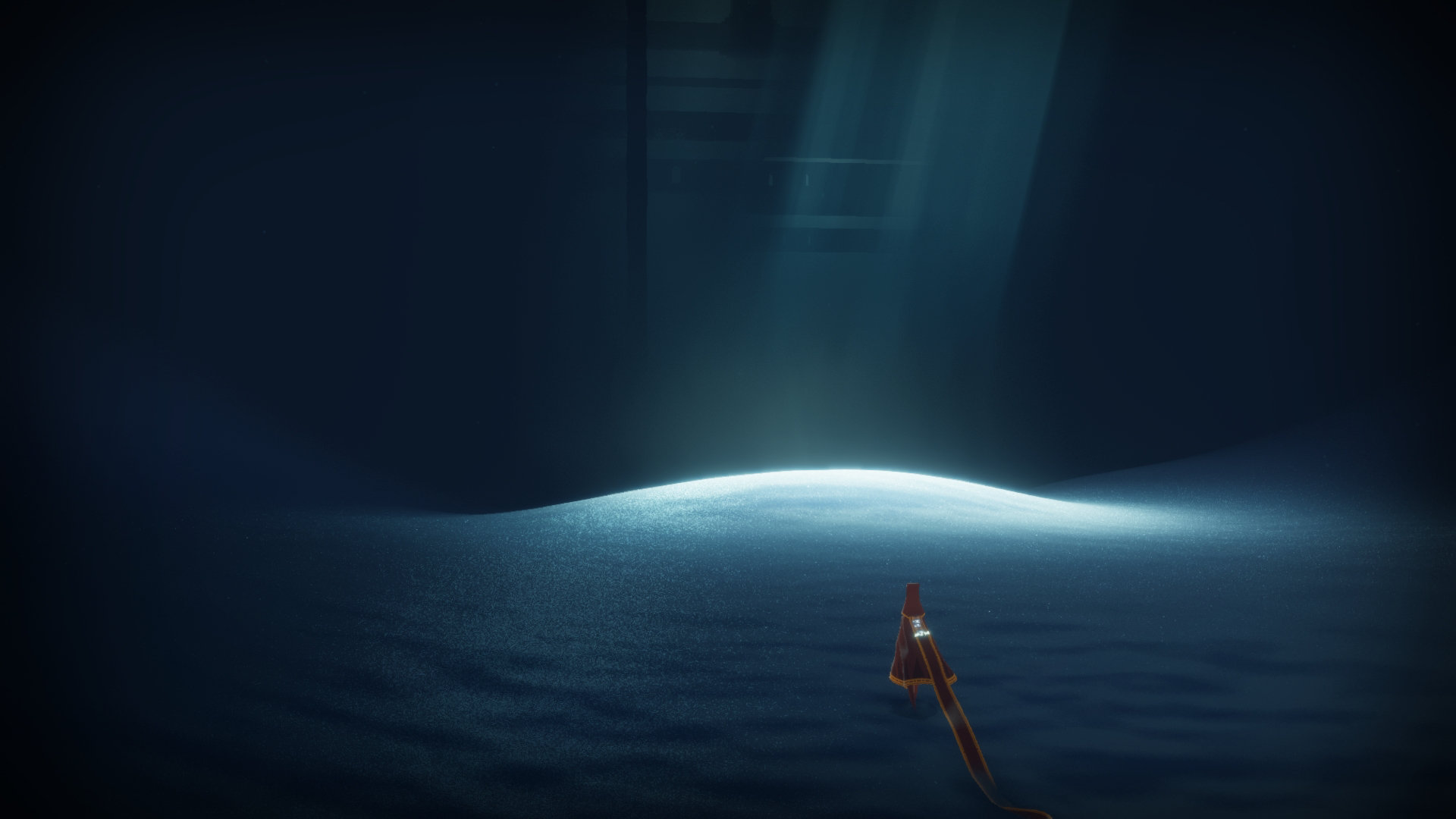

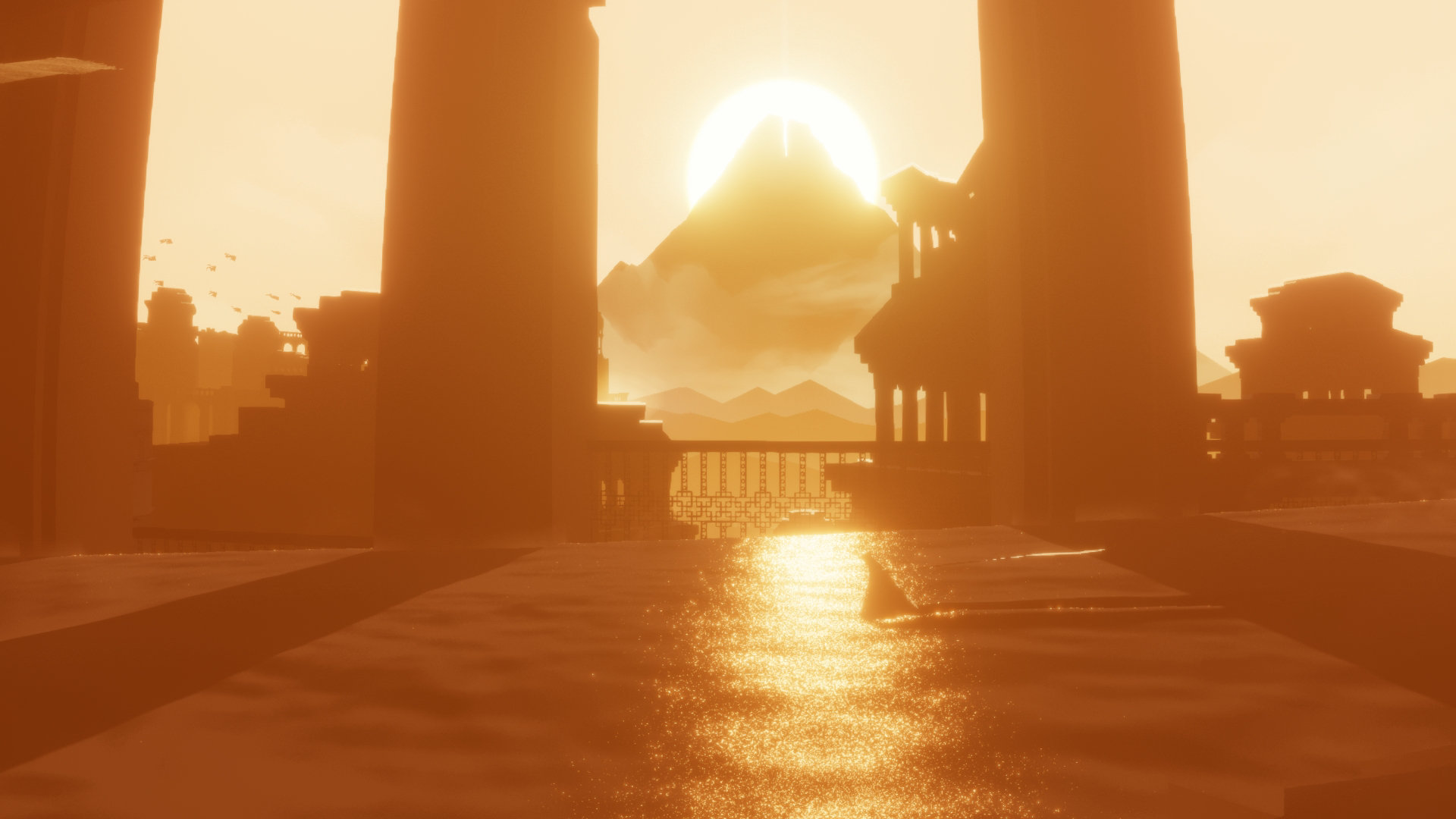

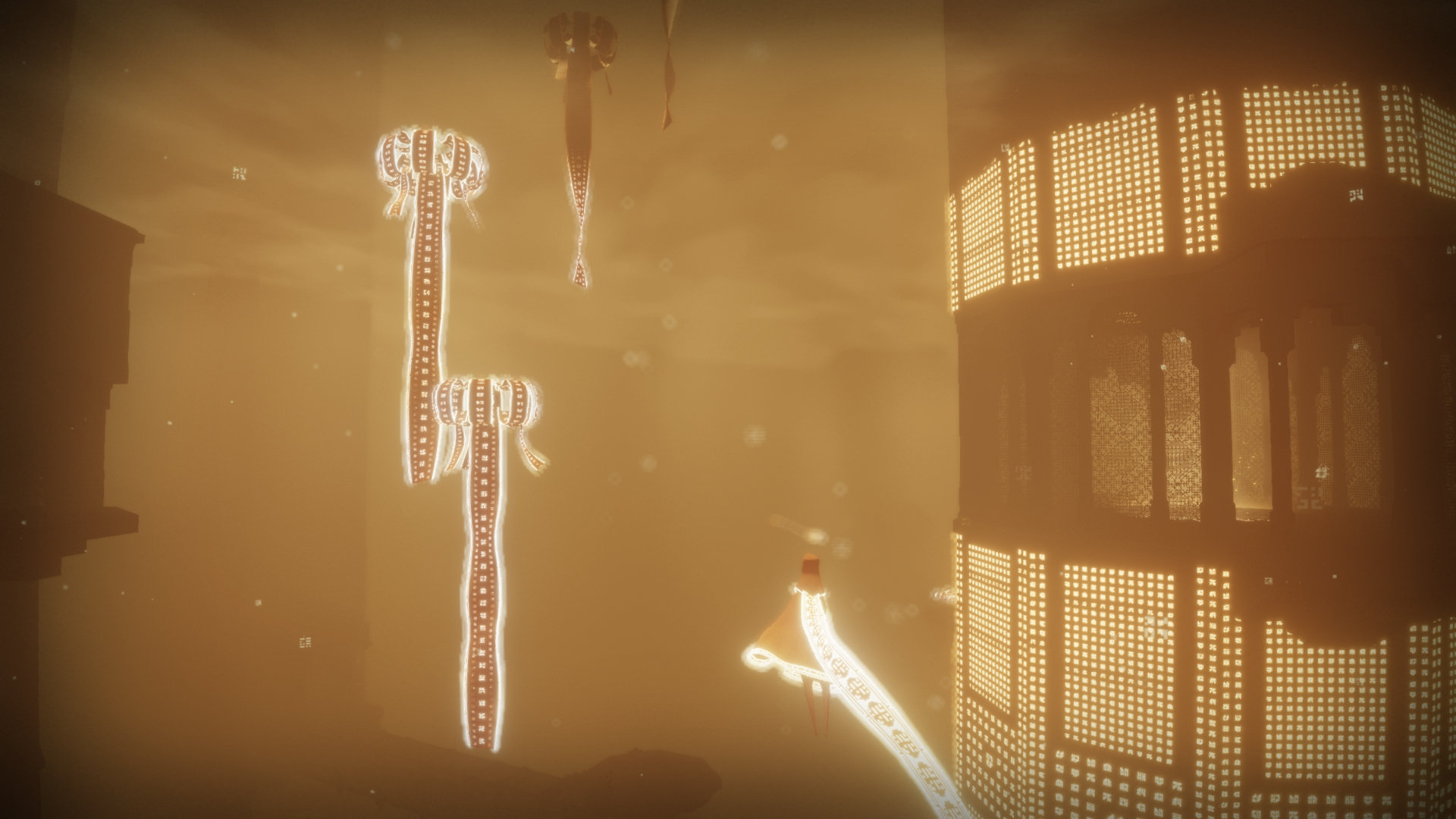

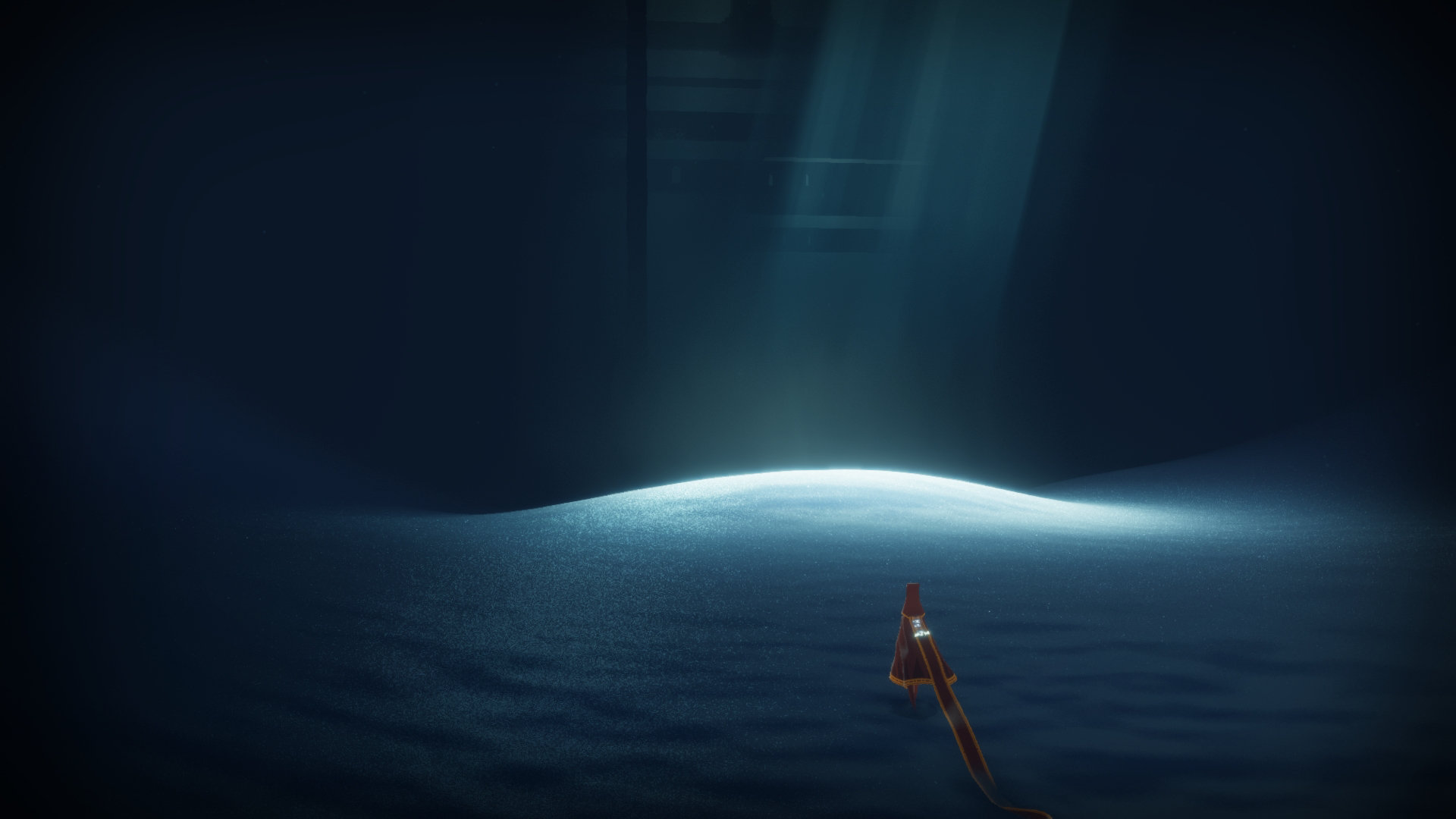

Journey

As this blog post makes clear, there are many games I’m very happy to evangelise about. But there’s only one game I’ve ever more-or-less forced my friends and significant others to play. Last but not least, let’s talk about Journey.

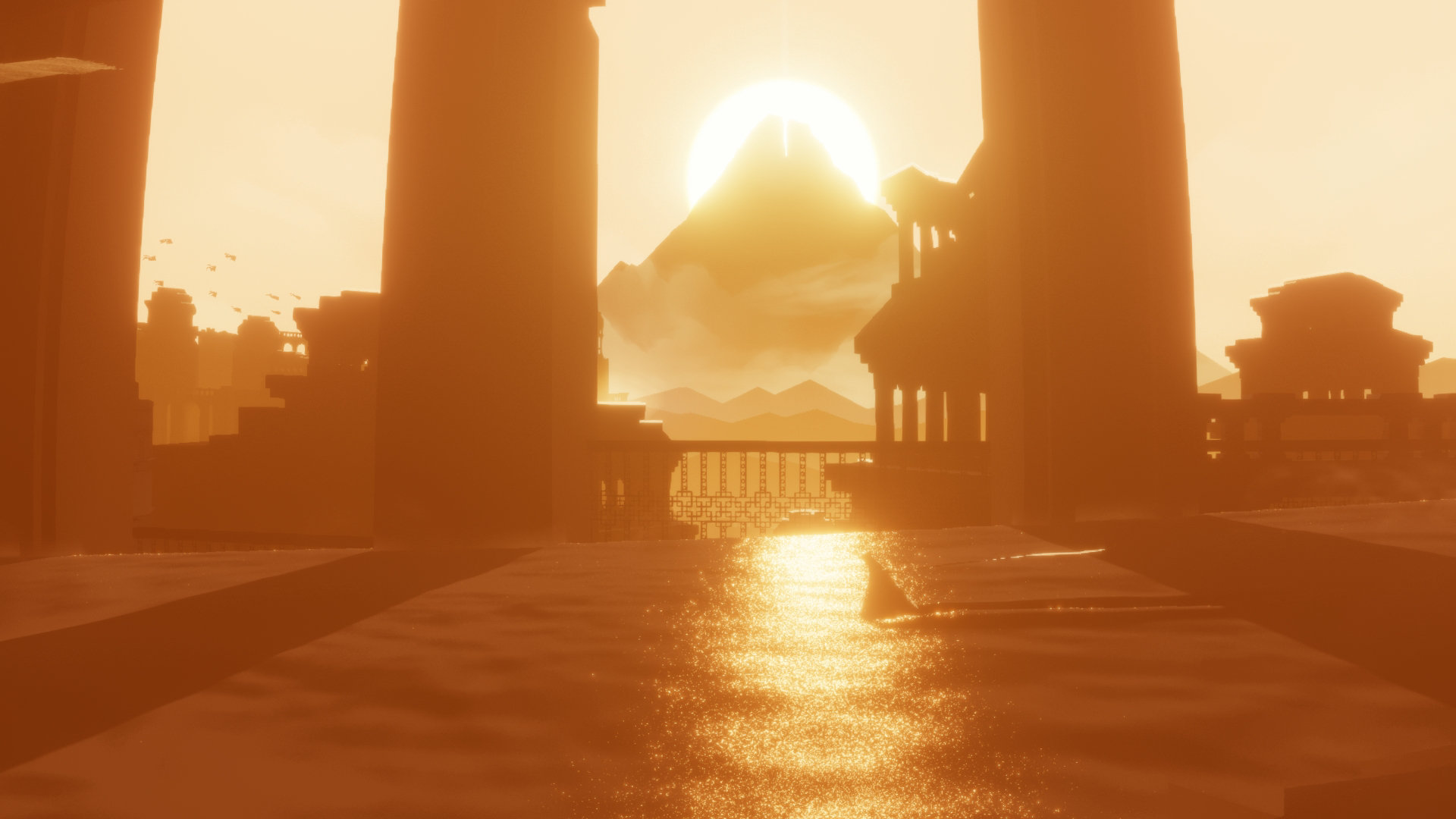

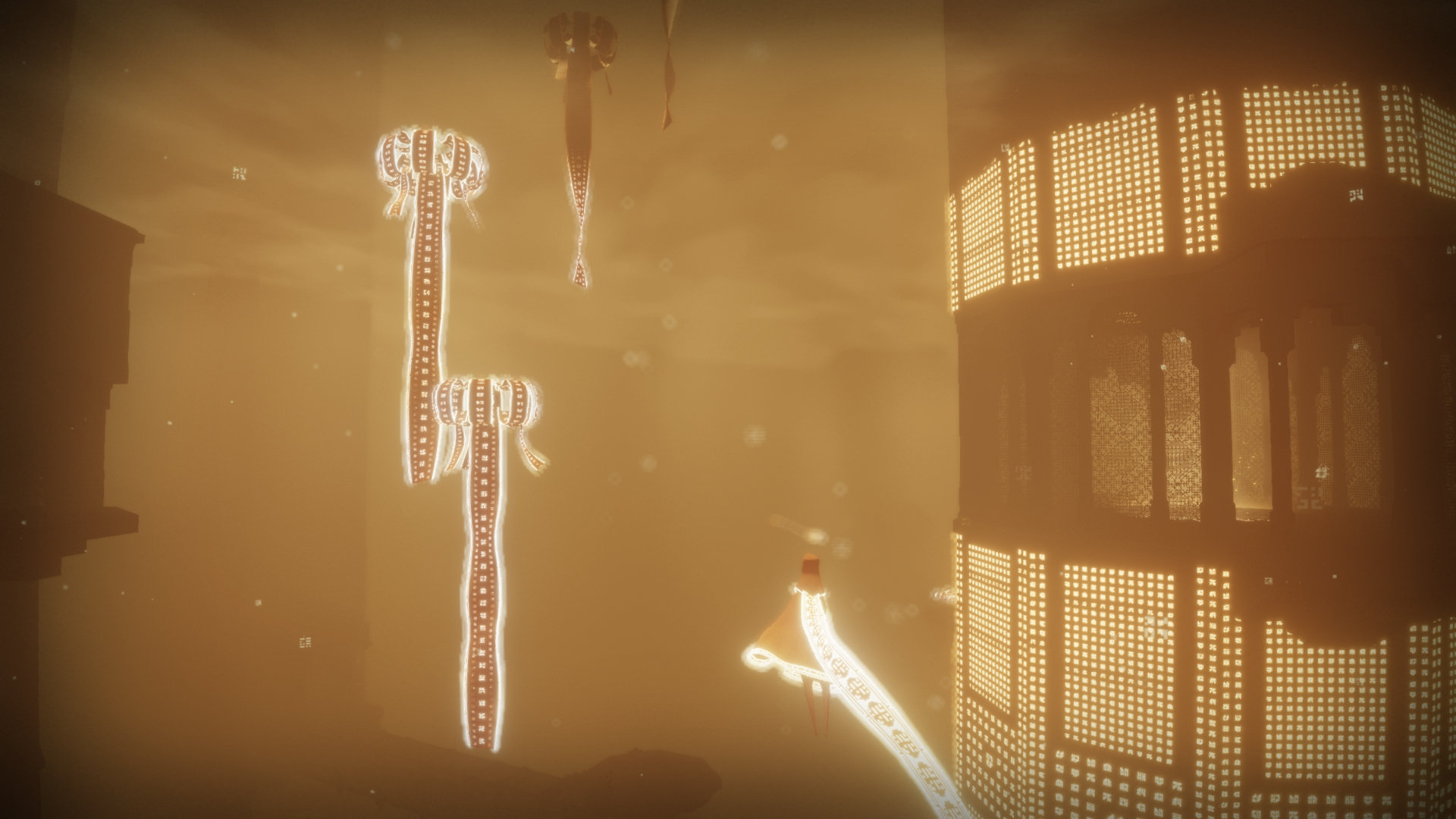

Journey’s beauty is, I think, uncontroversial. It is also many-faceted. The style of its ruined art and architecture – some mashup of ancient Egypt, classical Islam, and Shadow of the Colossus – is big and solemn and imposing, a fitting match to the solemn grandeur of the desert, and of the everpresent mountain. The game’s use of light and shadow is masterful, conjuring powerful and repeating cycles of safety and danger, purity and corruption, good and evil. The music is great, especially the song that plays over the closing credits, soaringly marking your…ah, but that would be telling.

But what really makes the game shine, quite literally, is the sand. I’ve never seen sand like this before, in the real world or any other game. I never get tired of watching it: it glitters like a sea of gemstones, shifting colours vividly from level to level as the light changes. The game reaches its first apotheosis at sundown, when the sand shines like gold against the enormous setting Sun. Just its first apotheosis, mind – there are more to come.

In addition to its visual beauty, Journey is also a masterclass in nonverbal storytelling. There is not a single word of dialogue in the entire game: you piece together the story from abstract, wordless visions and long-abandoned murals. You need to go slowly and carefully – or play several times – to really understand what’s going on, but once you do it adds a layer of once-hidden meaning to everything you see. There is no other game I enjoy watching other people play as much as this.

Gameplay wise, Journey is simple: a little more mechanically complex and involved than a walking simulator, a little less than any other kind of game. Yet despite their simplicity the mechanics work wonderfully. Jumping and gliding are joyful; failing and falling hurt. I was particularly impressed by the game’s mechanics of gameplay and loss: you can’t die, so you’d think the game’s enemies would hold no fear, but in fact they can harm you far more enduringly and meaningfully than in a game with higher lethality and at-will saves.

Mind, that’s in the PS3 version. For all I know the PC version has at-will saving and so has given up that particular gem of design. But! As of 2020 there’s a PC version on Steam, which you should all immediately go and buy. I can’t physically sit you down in front of my TV and hand you a controller, but this is me doing it in spirit: buy Journey. Play it. Share it with your friends. Spread the good word.

Oh, and those other games I mentioned up above are pretty good too. Maybe check those out while you’re at it.

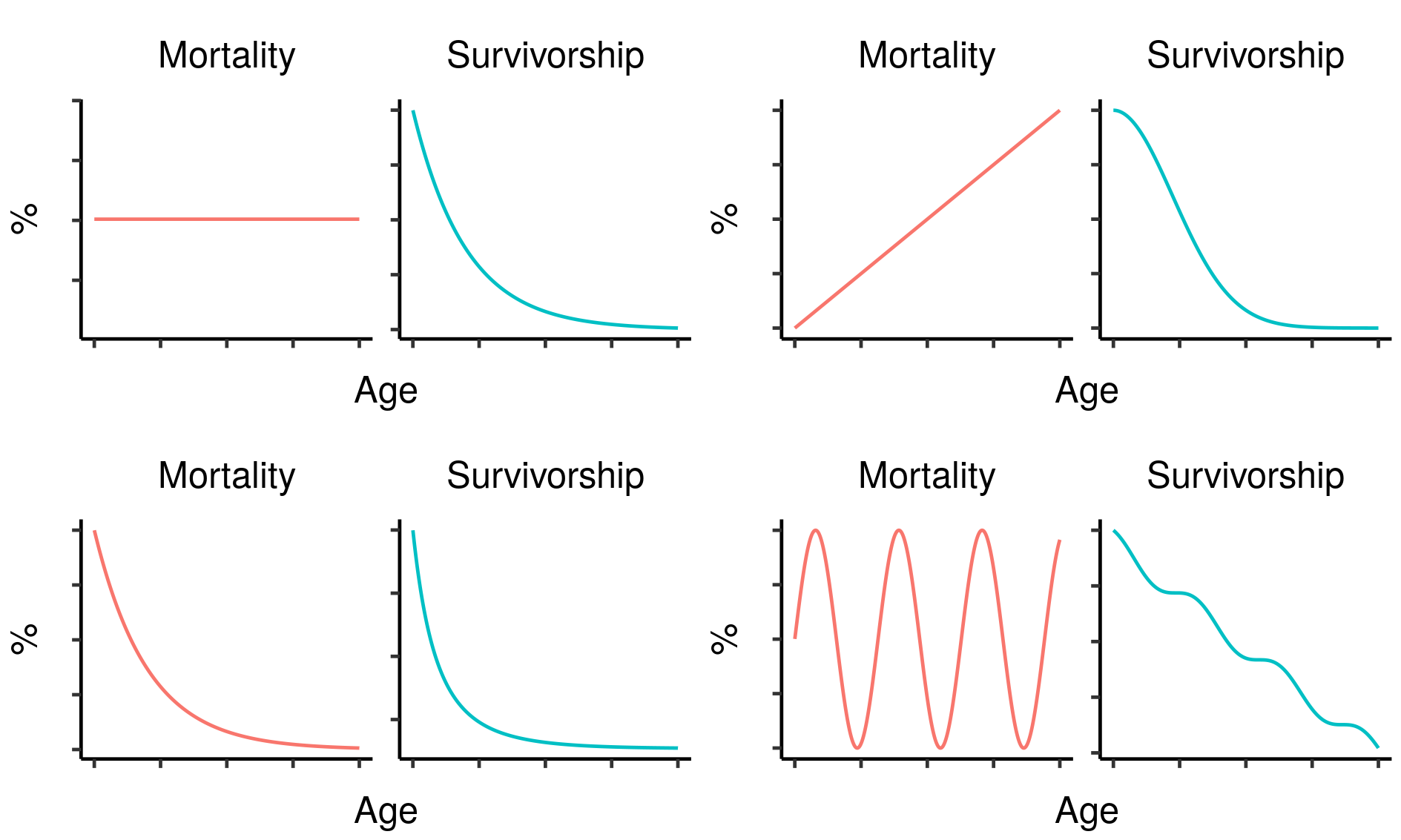

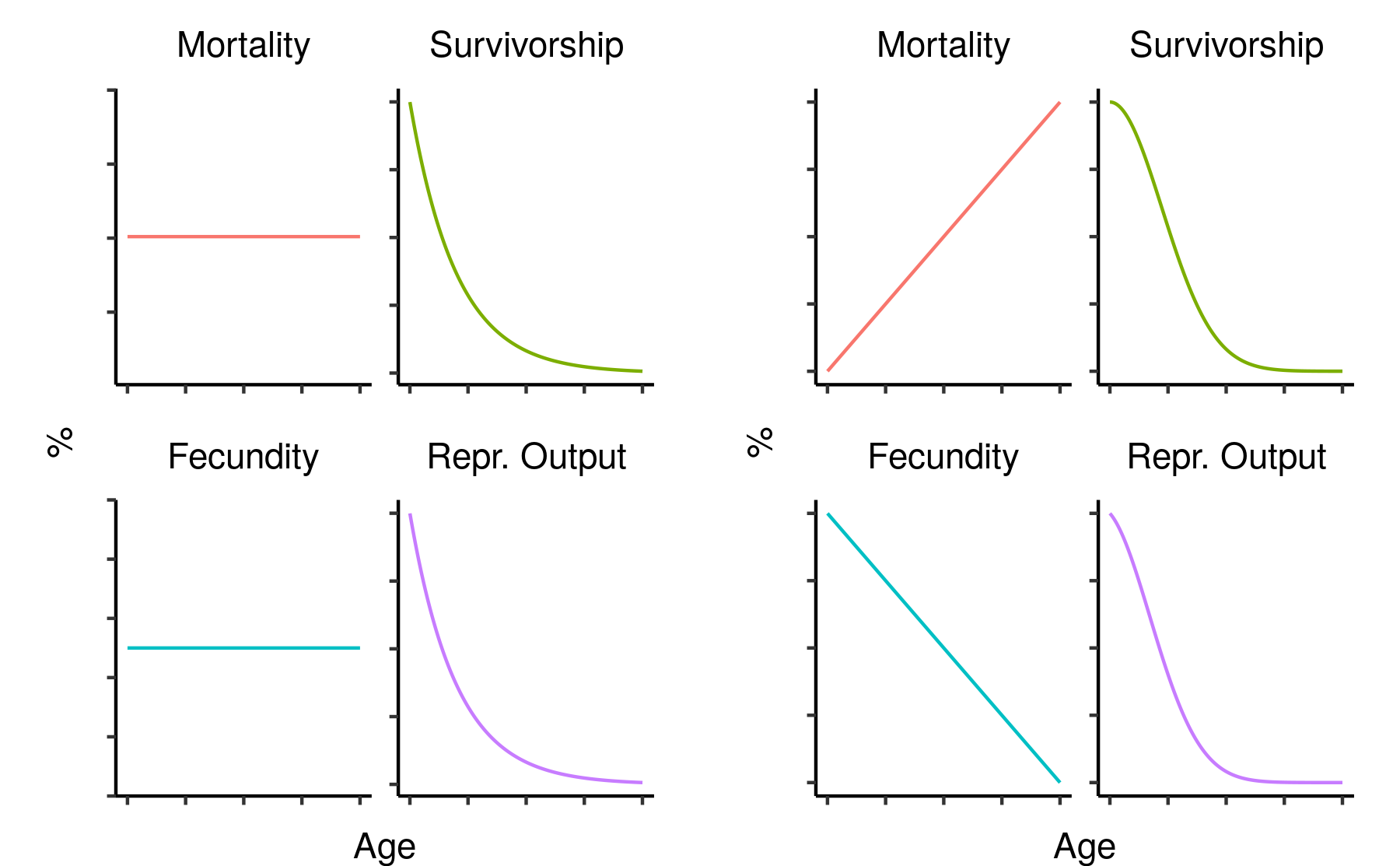

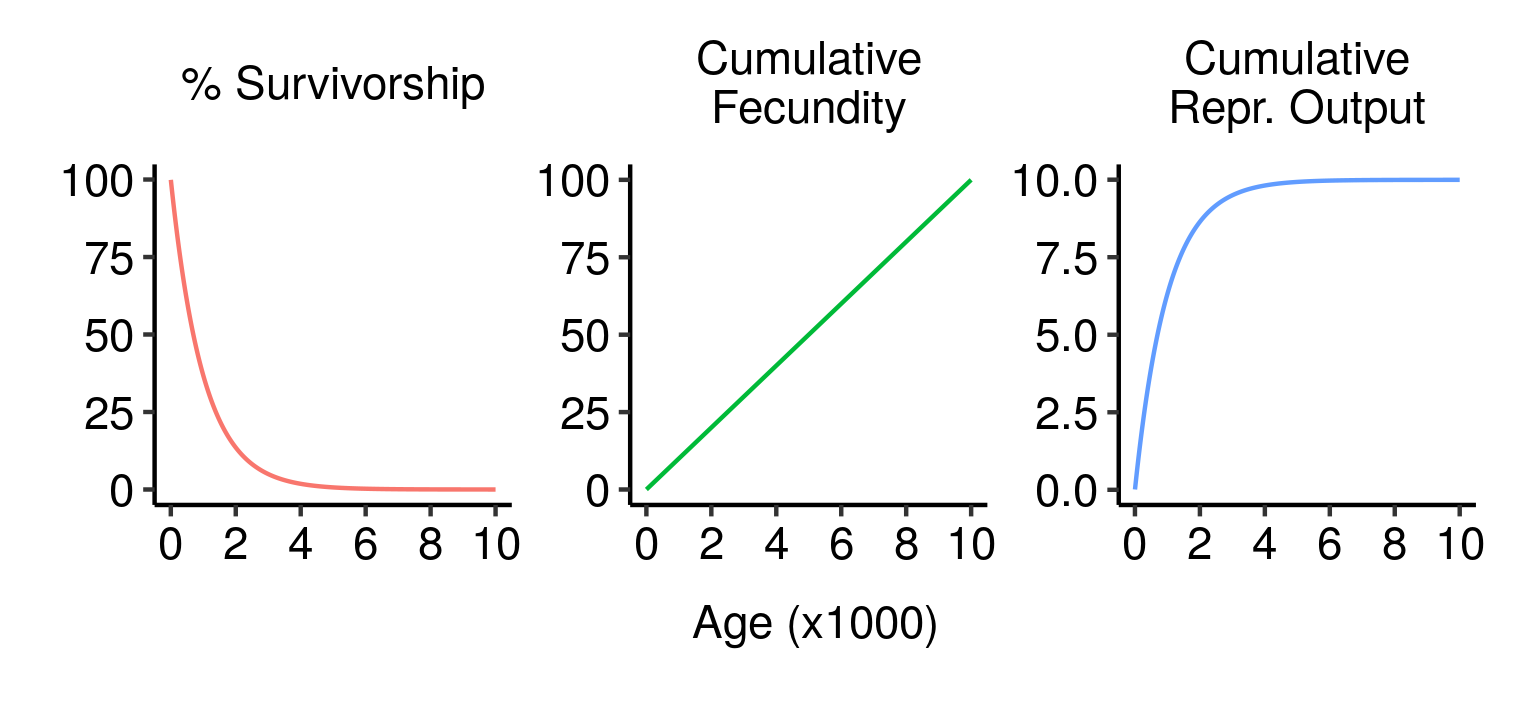

Survivorship, cumulative fecundity and cumulative reproductive output curves for a population of elves with 1% fecundity and 0.1% mortality per year.

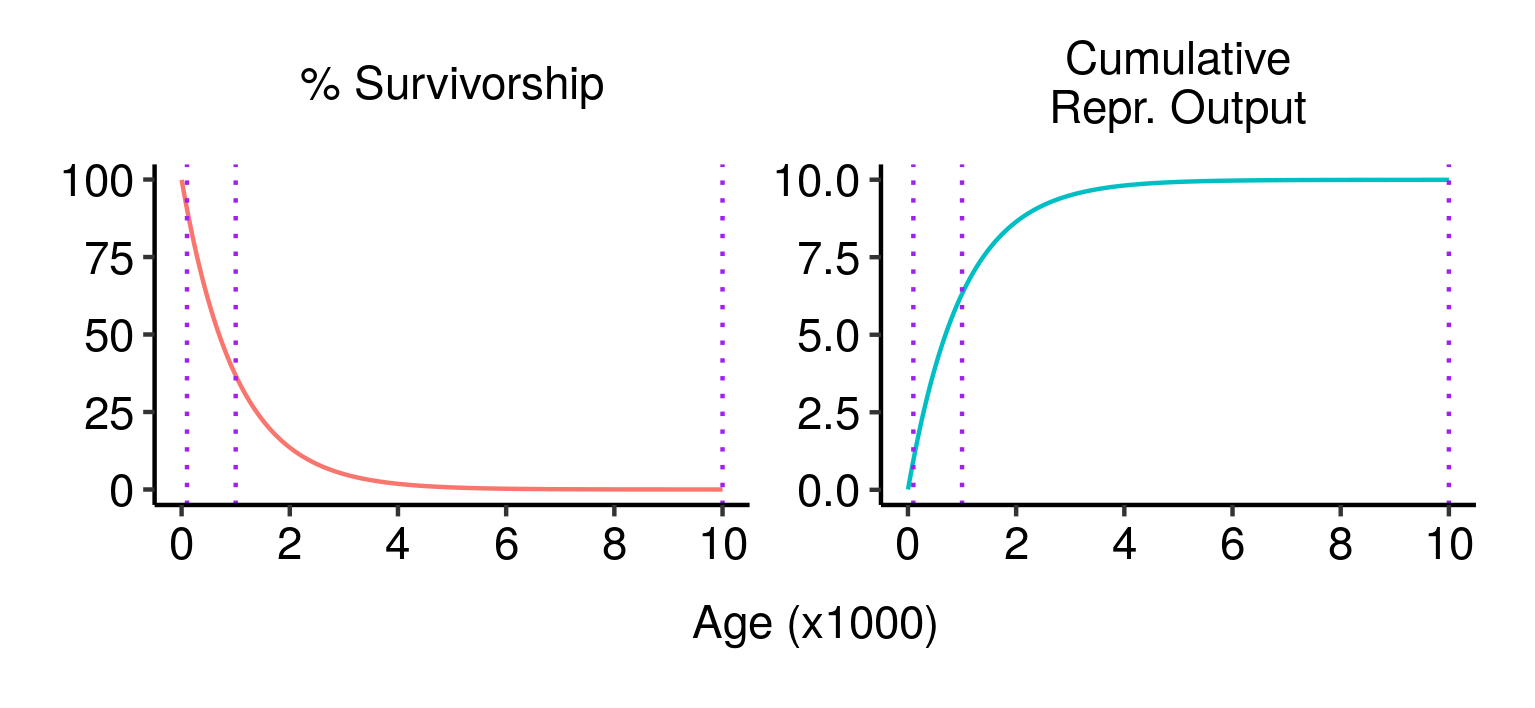

Survivorship, cumulative fecundity and cumulative reproductive output curves for a population of elves with 1% fecundity and 0.1% mortality per year. Three potential fatal mutations in the elven populations, and their effects on lifetime reproductive output.

Three potential fatal mutations in the elven populations, and their effects on lifetime reproductive output. Age-specific survivorship as a function of different levels of constant extrinsic mortality.

Age-specific survivorship as a function of different levels of constant extrinsic mortality.

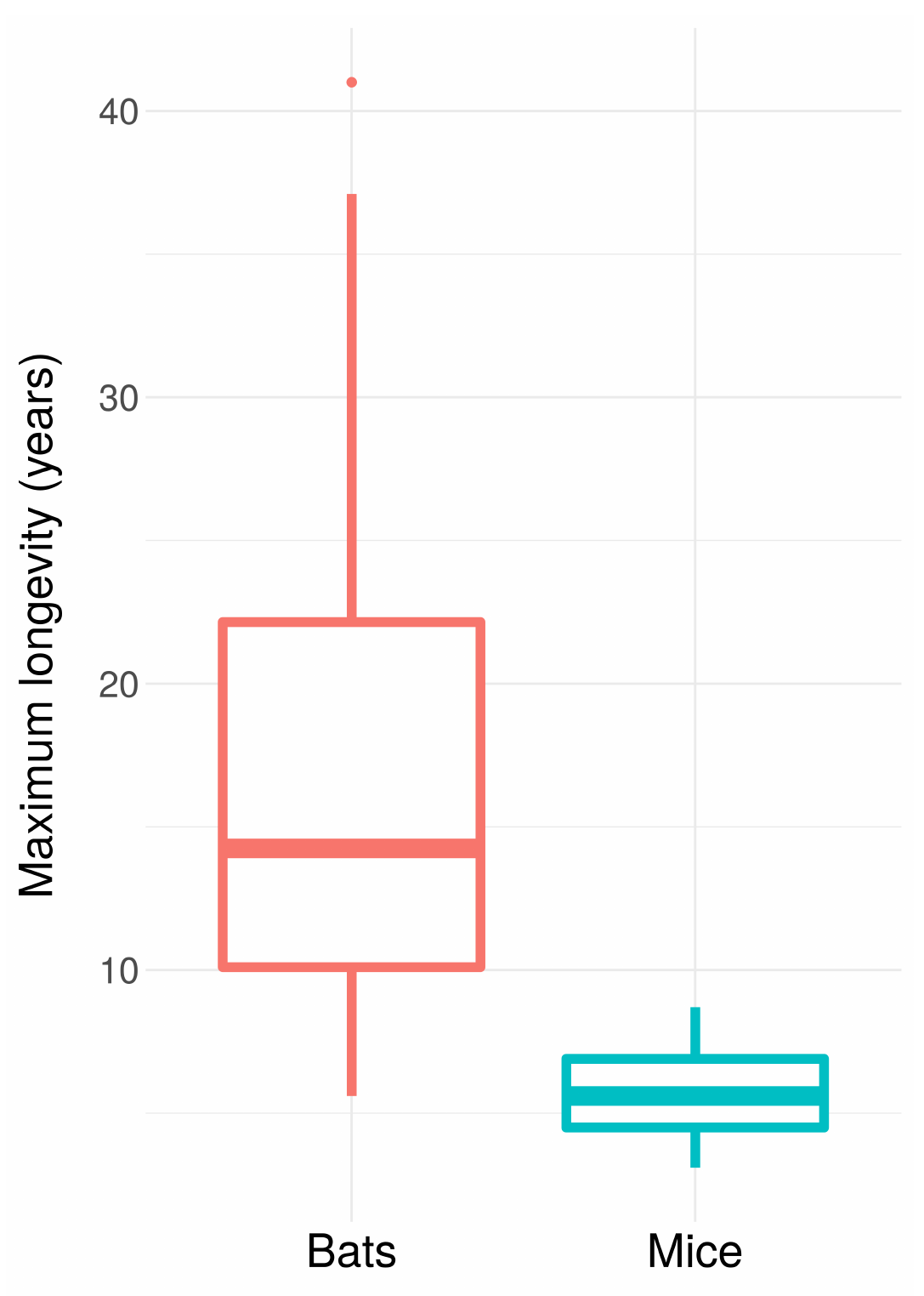

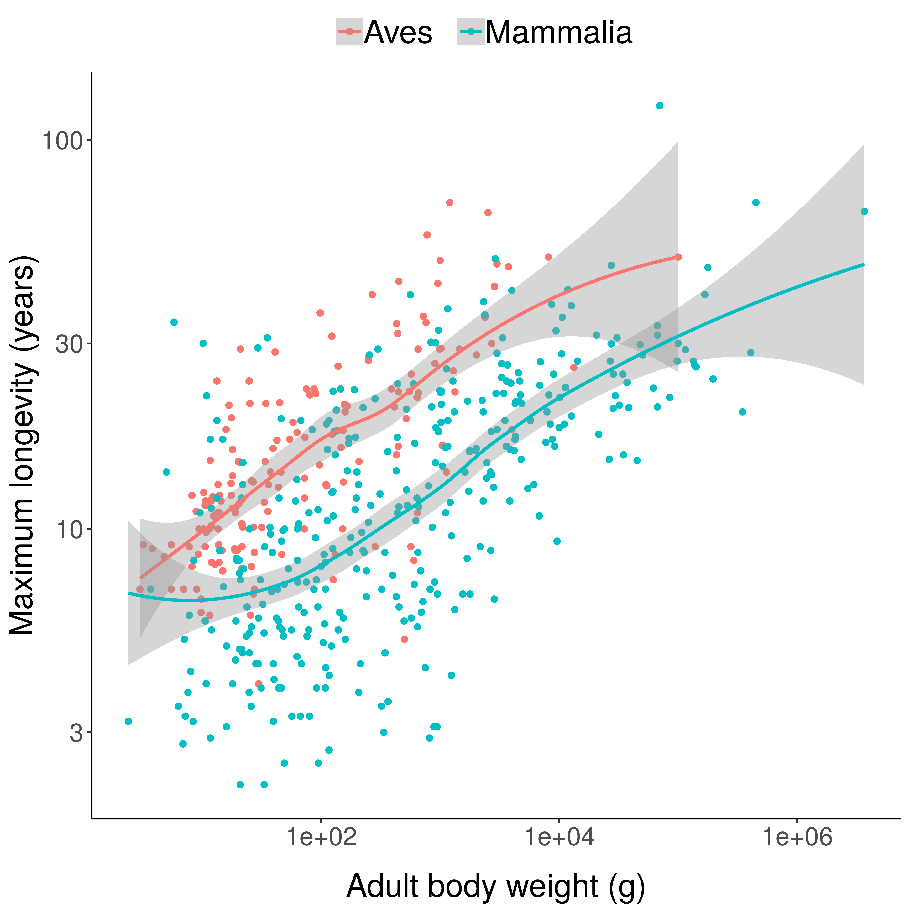

Scatterplots of bird and mammal maximum lifespans vs adult body weight from the AnAge database, with central tendencies fit in R using local polynomial regression (

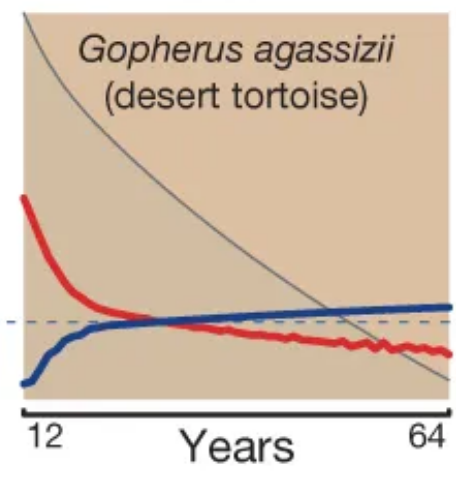

Scatterplots of bird and mammal maximum lifespans vs adult body weight from the AnAge database, with central tendencies fit in R using local polynomial regression ( Mortality (red) and fertility (blue) curves from the desert tortoise, showing declining mortality with time. Adapted from Fig. 1 of

Mortality (red) and fertility (blue) curves from the desert tortoise, showing declining mortality with time. Adapted from Fig. 1 of